Authored by

Lorenza Gervasio

Antonio Tria

Executive Summary

Nigeria’s demographic history is long and multifaceted, shaped by both traditional cultural norms and contemporary socio-economic pressures. Like many Sub-Saharan African nations, it is characterized by widespread poverty, inequality, and uneven development.

This report provides an in-depth analysis of Nigeria’s past and present demographics, offering insights into age structure, life expectancy, fertility, migration and the environmental factors. Using a combination of existing literature and recent data, it also outlines projections for future population growth and distribution. The major focus of the report is the relationship between demographic dynamics and cultural beliefs. Practices about family size, gender expectations, and communal responsibilities impact fertility trends, access to education, and the healthcare system. Although these factors are often overlooked, they play an effective role in shaping the effectiveness of policies for Nigerian development.

The report proposes several key policy recommendations to address Nigeria’s challenges. First, coordinated investments in health, education, and employment are essential to capitalize on the growing working-age population. Expanding access to family planning, improving maternal healthcare, and addressing early marriages are crucial. Education, particularly for girls, and investments in school infrastructure must be prioritized. Vocational and technical training, alongside legal and financial reforms, are necessary to drive economic growth. Social protection policies should focus on the most vulnerable, especially the rural poor and female-headed households. Policies should balance urban and rural development, addressing migration and environmental challenges, with good governance, reduced corruption, and gender equality at the core of these efforts.

Addressing Nigeria’s demographic dynamics requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates cultural, economic, and social considerations. Effective policy implementation, guided by a deep understanding of these complexities, will be essential in achieving sustainable growth. By focusing on strengthening healthcare systems, improving education, and supporting inclusive economic policies, Nigeria can pave the way for a more prosperous future. It is crucial that both national and international efforts continue to align in support of Nigeria’s development, ensuring that the country’s demographic potential is fully realized for the benefit of its citizens and the broader African region.

* All data used for graphs and tables are retrieved from the United Nations World Population Prospects 2024 and personally elaborated by the authors. When data are retrieved from other sources, it is specified in related notes

Introduction

Located in Western Africa, Nigeria is regarded as the most populated African, currently estimated at 237.5 million.[1] Nigeria, with the capital in Abuja, faces the Gulf of Guinea and borders Cameroon, Benin, Ciad, and Niger. Nigerian demographic analysis is multifaceted and shaped by numerous events. 1960 was a turning point, as the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, with a population growth rate that peaked from 2% to 3.1% in 1980.[2] However, the years following independence saw corruption, instability, and violence from the Second Republic government, along with a sharp decline in oil revenues, leading to a 1983 coup d’état by the military.[3] Consequently, the population growth rate dropped to 2% in 1983, slightly increasing until 2.6% with democratization in 1999, and then steadily decreasing to 2.1% in 2024.[4]

Population growth has long been a major concern both globally and locally, directly affecting resource availability and development. While no consensus exists on its economic impact in developing nations like Nigeria, the country’s rapid and uneven demographic trends have not always produced positive outcomes.[5] In 1798, Thomas Malthus, in An Essay on the Principle of Population, first analyzed the unintended consequences of unchecked population growth and resource limits. According to Malthus, if “preventive checks” such as population control fail, then “positive checks” like wars, natural disasters, and famine will occur. Opposing theories argue that a large population boosts labor supply, hence stimulating growth.

Although Malthusian theory was disproved after the industrial revolution, developing countries have experienced – or still face – a Malthusian Trap. In Nigeria, rapid population growth worsened poverty, food insecurity, disease outbreaks, and social instability. Technological progress and control efforts have not overcome these effects due to weak agriculture, dependence on resources, and insufficient preventive measures.[6] Therefore, in this report we analyze Nigeria’s population dynamics, explore socio-economic and cultural factors overtime, and propose policies for a sustainable population development.

Population dynamics: including past, present, and prospects

Increasing population results from three key factors: birth rate, death rate and higher net migration. Migration has played a negligible role in Nigeria’s population growth. Although the CDR declined from 26 to 11 between 1960 and 2023, the CBR did not see the same rapid reduction until the last decade, when it dropped below 40 for the first time, indicating a rapid population growth.

Several factors contribute to Nigeria’s high demographic momentum, including religious beliefs, customs, and superstitions. Many Nigerian religions encourage large families, early marriage, and polygamy while prohibiting effective birth control methods such as contraceptives and family planning. Early marriage extends women’s reproductive years, increasing their potential to have more children. A cultural preference for male children – due to family prestige, physical labor, and old age social security – often leads to continued childbearing. Additionally, high illiteracy rates, particularly among women, worsen poverty, disease, homelessness, and unemployment, while increasing teenage pregnancy and fertility rates, contributing to overpopulation.[7]

- Age Structure and Demographic Transition

Currently, about 41.5% of the population is under the age of 15, 55.5% is between 15 and 65, and only 3% is above 65 years.[8] This age structure reflects the country’s high fertility rates, which are not expected to reach replacement level before 2070. Despite a recent decline in TFR, Nigeria’s population remains young, placing significant pressure on education, healthcare, job creation, and social security systems.

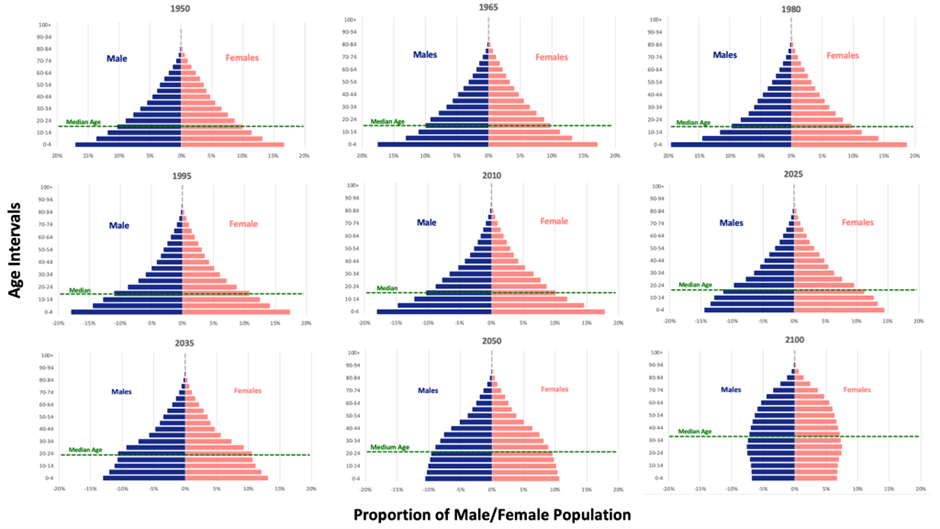

Note: Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of the Nigerian population overtime by gender. The pyramids display age groups on the Y-axis. It depicts the percentage of total population on the X axis. The blue bars reflect the data for males, the pink ones the data for females. Of the nine panels, the first five panels show the progression at 15-year intervals since 1950, the sixth includes current available in the data (2025) and the last row shows the expectations for three important milestones (2035, 2050, 2100). Data for Figure 1 was retrieved from the World Population Prospects 2024, United Nations. Graphic elaboration of the authors.

Since 1950, when the first available data was recorded, Nigeria’s population has been characterized by a consistent increase in the number of births, as shown by the large base of pyramids. Recent evidence, however, shows an emerging slowdown in this growth trajectory, indicating a gradual reduction in the proportion of young people within the population, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the share of elderly individuals. Although this shift is expected to unfold over several decades, the median age is projected to rise from its current value of 17.9 years to 23.9 years by 2050.

While the young age structure of Nigeria can present a challenge to be able to provide the necessary investments to cater for population growth, it however provides an opportunity for the country to reap from the demographic dividend.

Nigeria’s Demographic Dividend

Nigeria’s population has gained significant demographic momentum, doubling over the past 30 years and showing a high population multiplier, with continued growth expected even if efforts toward family planning and birth control increase, potentially affecting socio-economic development.

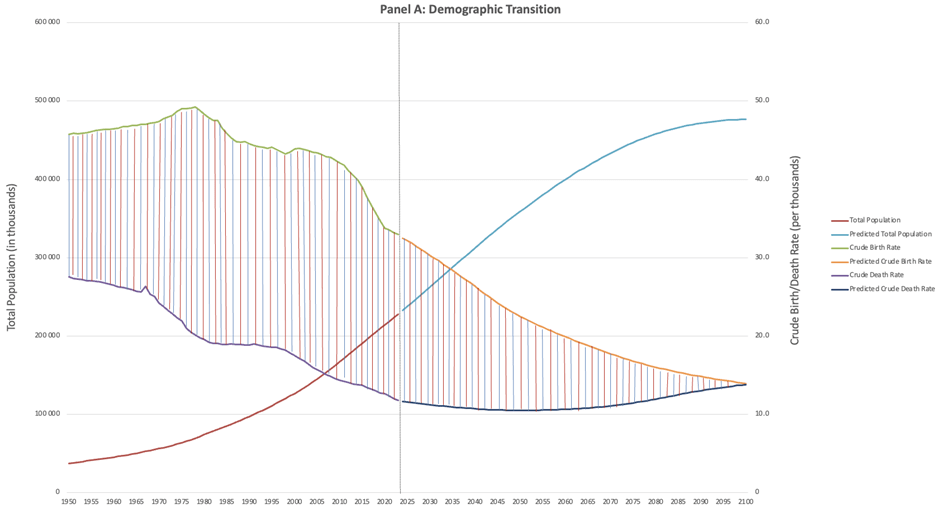

Note: Figure 2, Panel A illustrates the evolution over time of key demographic variables in Nigeria. Only the Medium-variant for each variable is plotted. The total population is calculated as the total number of individuals. The crude death (birth) rate as number of deaths (births) occurring during the year, per 1,000 population estimated at midyear. The graph shows the evolution of the variables from 1950 to 2100. The vertical line indicates the last year before the data turns into predicted data. The shadowed area indicates the evolution of the demographic dividend. Panel B replicates the figure of Panel A but including Low and High-variant estimations. Data for Figure 2 was retrieved from World Population Prospects 2024, United Nations. Graphic elaboration of the authors.

As generally defined, demographic dividend occurs when a decline in mortality precedes a large decline in fertility. Nigeria is in the middle of the demographic transition, and at this stage, often known as the “baby boom,” the age structure of the population ultimately changes, leading to a working age bulge once this large cohort of children grows up. Consequently, fewer investments are needed to meet the needs of the youngest age groups and resources are released for investments in economic development and family welfare.[9]

Dependency Ratio

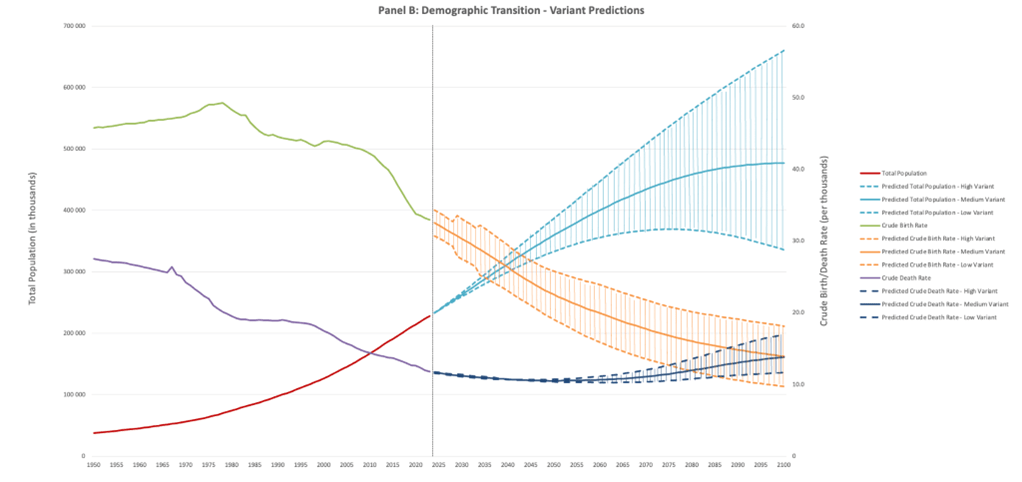

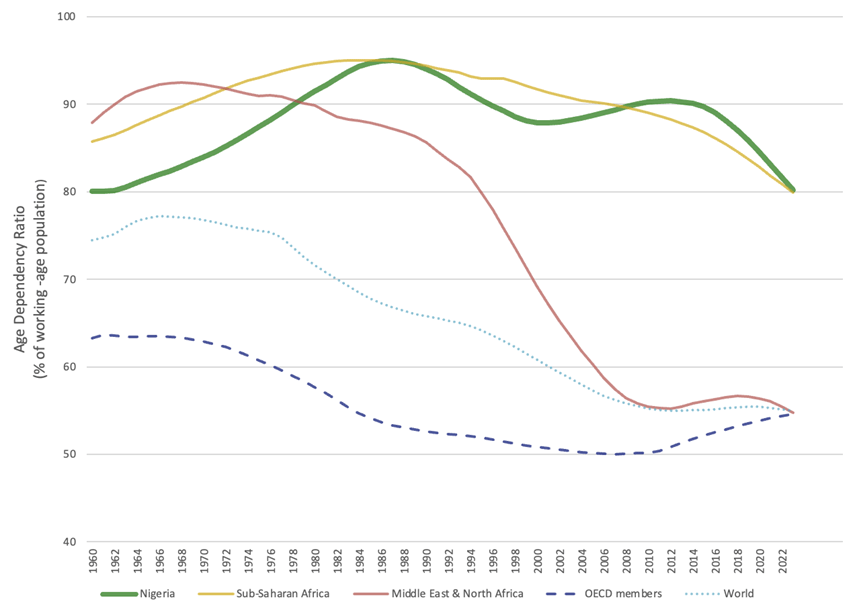

By 2050, Nigeria’s population is projected to reach 357 million, according to UN Medium-variant estimates, with a growing share entering the working-age bracket. Over the past decade, the dependency ratio has declined from 90.4 to 80.24, reflecting a demographic shift driven largely by a reduction in TFR. This “demographic bonus”indicates a rising proportion of the working-age population (defined as individuals aged 15–64) relative to dependents, signaling a crucial phase in the demographic transition.

Note: Figure 3 illustrates the evolution over time of the age dependency ratio for a subsample of regions (division of subsample explained below)[10], in terms of working population (15-64). Data for Figure 3 was retrieved from World Bank estimates based on the World Population Prospects 2024, United Nations. Graphic elaboration of the authors.

However, whether the labor force cohort constitutes a dividend or not also depends on the availability of employment. A large working-age population that remains underemployed or unemployed becomes a strain rather than a support. Therefore, while the current demographic profile constitutes an important window of opportunity, its benefits rely on the effective transformation of this population into an educated, skilled, and economically active workforce, ensuring that the demographic shift translates into tangible societal progress.

- Life table, Mortality, and Survival

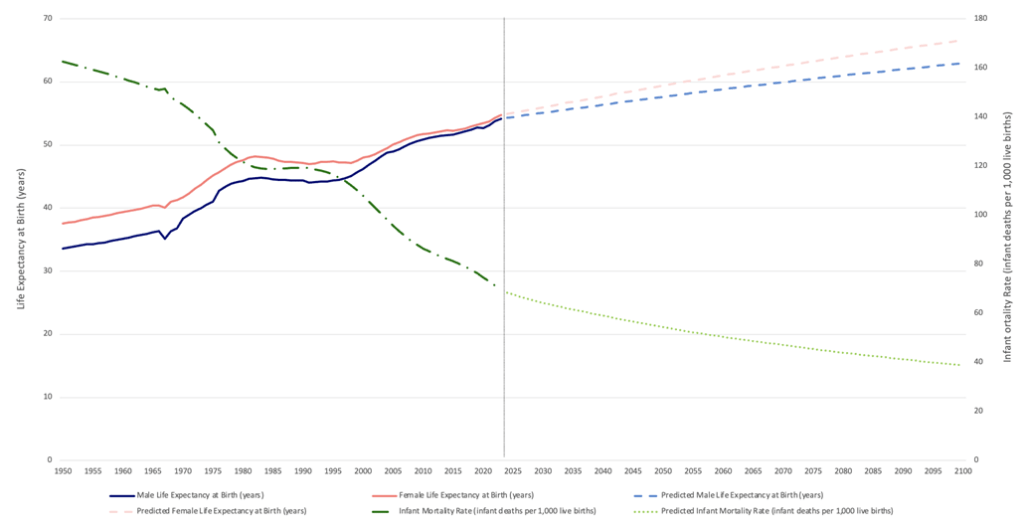

Note: Figure 4 illustrates the evolution over time of life expectancy (years) and infant mortality rate (deaths per 1000 live births). Figure 4 shows the evolution of the two variables during the period 1950-2100. The vertical line indicates the last year before the data turns into predicted data. The figure aims at depicting the relation between life expectancy and infant mortality. Data for figure 4 was retrieved from the World Population Prospects 2024, United Nations. Graphic elaboration of the authors.

Human Development Index (HDI)

The HDI is an index of life expectancy, literacy, and per-capita GDP measuring a country’s socio-economic development.[11] Although the African continent is making some progress in healthcare and welfare – raising Nigeria’s HDI by 22% in the last 19 years – it remains low at 0.548. As a comparison, Italy reached 0.906 in 2022.[12] A UNDP report attributes this gap largely to persistent gender disparities and a high level of multidimensional poverty at 33%.[13]

Epidemiological Transition

Alongside the demographic transition, the epidemiological transition describes how countries’ main causes of death shift over time. Historically, death was largely caused by poor living conditions and epidemics, but today, particularly in the Western world, chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are the leading causes. In Nigeria, however, neonatal and maternal conditions account for over 50% of deaths.[14]

Social and medical determinants of mortality should be prioritized in policymaking, as 145 women die daily from childbirth in Nigeria. Medical, behavioral, social, and cultural beliefs contribute to maternal mortality. The “Three Delays Model” in Nigerian healthcare shows delays in identifying complications and birth preparedness at the household or community level, reaching healthcare due to logistics and transport, and accessing quality medical facilities. These issues severely impact women’s health during childbirth, making it a leading cause of mortality in Nigeria.[15]

Cultural Beliefs: The Abiku Mythology

Nigerian mortality literature highlights the role of cultural beliefs. In regions where Yoruba tribes live, under-five mortality is high due to Abiku beliefs. The myth holds that Abiku – spirit children – die young and move between the earthly and the spiritual worlds. A 2004 study interviewing 1695 women found that many believe Abiku children should not be treated like others, leading to delayed or avoided medical care. This worsens illnesses like measles and malaria.[16] The key takeaway is that without integrating local belief systems into interventions, efforts to reduce mortality may prove ineffective.

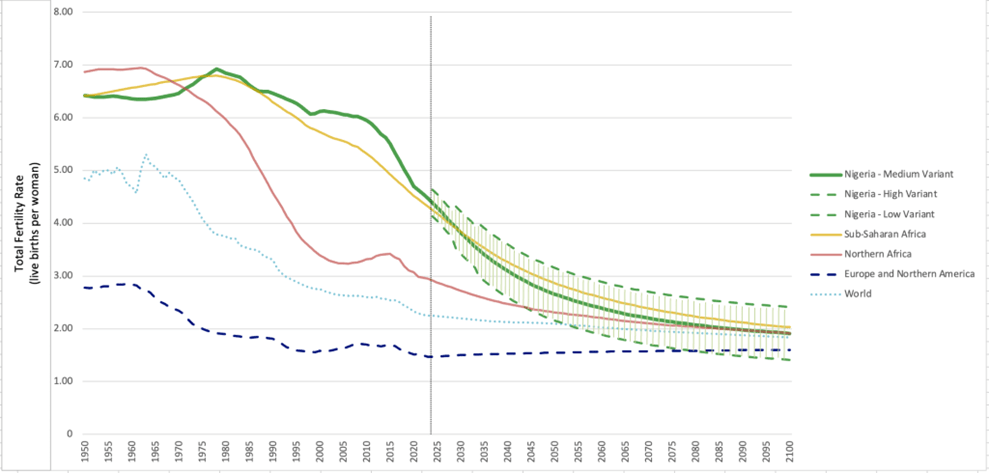

- Marriage and Families

Note: Figure 5 illustrates the evolution over time of the TFR for a subsample of regions (division of subsample explained below), in terms of live births per woman. Figure 5 shows the evolution of total fertility rate during the period 1950-2100. The vertical line indicates the last year before the data turns into predicted data. Data for Figure 5 was retrieved from the World Population Prospects 2024, United Nations. Graphic elaboration of the authors.

In the last 10 years, Nigeria’s TFR has seen a notable decline, approaching the third phase of the demographic transition. However, like many African states, it remains high. Nigeria’s fertility transition faces a dilemma: economic development versus social norms. Although smaller families are linked to higher parents’ expectations for their children and economic growth, social and cultural obligations are the main obstacles towards this transition. The most common kinship obligation is the belief that a larger family means more power and wealth.[17]

The decline in fertility is linked to improved contraceptive methods, though access remains unequal. CPR rose from 8% in 2003 to 20.3% in 2024 among married women and 50% among sexually active unmarried women.[18] However, benefits are not equally shared: urban, educated women use contraceptives more than disadvantaged groups.[19] Fertility is much higher in rural areas, where women have an average of 5.6 children compared to 3.9 in urban areas. While fertility studies often focus on women, men’s role must also be considered. Indeed, Nigerian men are skeptical of fertility decline, as delays in marriage and parenthood challenge cultural ideals of masculinity.[20]

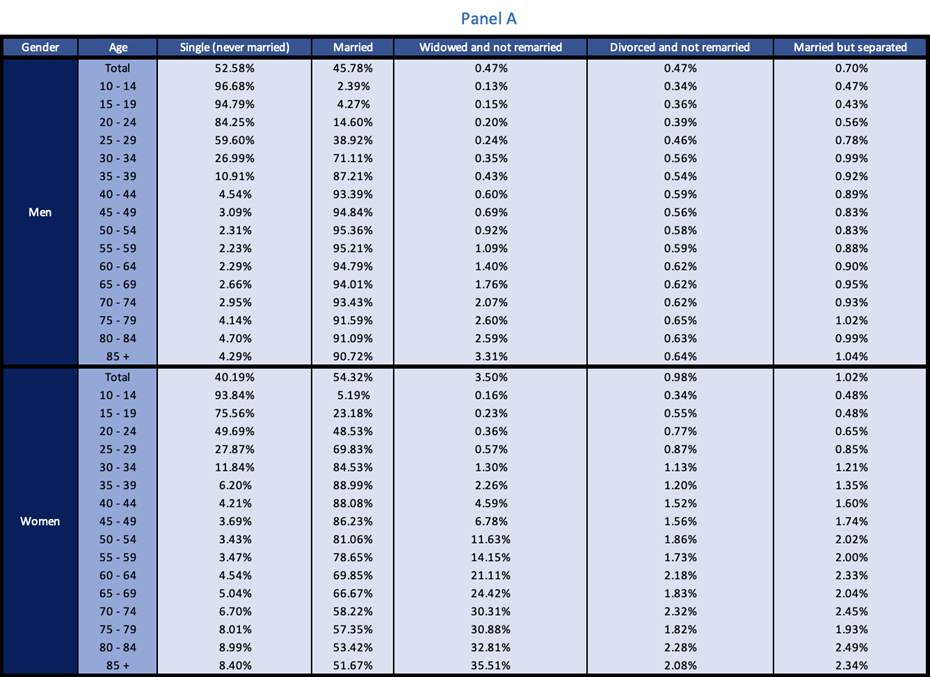

Note: Panel A: data retrieved from the United Nations Statistic Division, Demographic Statistics Database (2006 National Survey). Panel B: data are retrieved from the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Nigeria, Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2023–24: Key Indicators Report. Panel A shows the Nigerian marital status by age and gender, differentiating between single, married, widowed, divorces, and separated. In Panel B the analysis is on met/unmet need for family planning among women. Graphic elaborations of the authors.

Panel A presents Nigeria’s marital status, showing that 52.58% of men are “never married,” compared to 40.19% of women, likely due to the higher prevalence of polygynous relationships among men. Additionally, Nigeria has a low divorce rate of around 2.9%, influenced by cultural norms that outweigh legal frameworks. Panel B reveals that 21% of married women and 36% of sexually active unmarried women have unmet family planning needs. Among married women, only 37% of demand for family planning is met with modern methods, while 44% of sexually active unmarried women have their needs satisfied in the same way.

Many Nigerian women have their first child before the age of 20, with around 36.8% of women having their first birth before 18.[21] Inequalities and gender gaps, driven by social norms, have significant household impact. Household economic conditions in Nigeria indicate that single adult households generally face more economic challenges, with female-headed ones most affected.[22]

Poverty is not the only consequence. In many African states, practices like FGC are deeply rooted in culture. While dismantling such beliefs is difficult, egalitarian households, where women have decision-making power, are more likely to abandon these inhuman practices, often passed down through generations.[23] The connections across fertility transition topics are deeply cultural, making education crucial in addressing many of Nigeria’s challenges rooted in traditional beliefs. Women with no education, informal or primary education have higher fertility compared to those who have attained secondary or tertiary levels of education.[24]

- Migration

In March 2025, Filippo Grandi, UNHCR High Commissioner, explained that most African countries, including Nigeria, experience a different form of migration compared to Europe. People typically migrate to nearby areas rather than traveling far, even when fleeing violence and instability.[25]

Internal Migration

The IOM 2024 report confirms that most Nigerian migrants move to neighboring states.[26] In 1960, only 16% of Nigerians lived in urban areas, but by 2023, that figure rose to 54%.[27] While democratization and independence have influenced migration patterns, internal migration remains more common than international flows. Economic opportunities, marriage, conflict, and environmental factors like soil erosion or floods are key drivers.[28] Among Nigerian male migrants, 72% relocate internally, while 28% migrate internationally. A larger proportion of female migrants, 81%, move within the country, with only 19% migrating abroad. Over 41.5% of internal migrants relocate in search of employment, 29.7% for educational opportunities, 26.7% for family reunification, and 1.9% for other reasons.[29]

Rural-urban Migration

Historically, internal migration in Nigeria has been dominated by rural-to-rural movements. In 2005, 62% of internal migrants moved between rural areas, while 37% moved from rural to urban zones.[30] Overtime, this trend was reversed, with rural-urban migration now more common, particularly among young Nigerians.

Rural-urban migration is now the prevailing internal migration pattern, influenced by education, gender, and ownership. Women and more educated individuals are more likely to migrate to cities due to higher expected returns. Those with greater land ownership also migrate, but typically for shorter periods, reducing the likelihood of permanent relocation.[31] As a result, urban areas in Nigeria are becoming overpopulated, straining social services and creating a mismatch between labor supply and job availability.

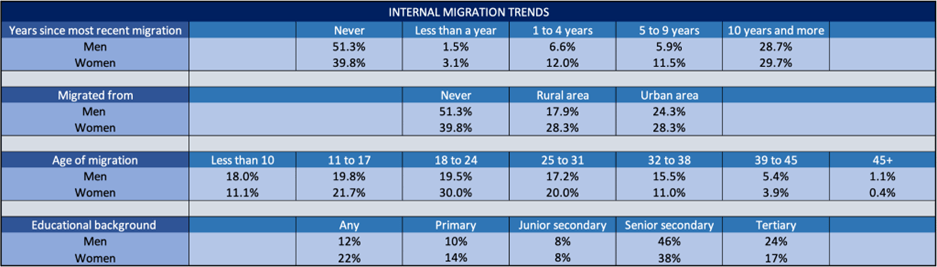

Note: Data are retrieved from the UN report International Migration Trends in Nigeria. Table 2 – elaboration of the authors – shows that men migrate more frequently and for longer periods than women. 28.7% of men migrated over 10 years ago, while women are 29.7%. Rural-to-urban migration is the most frequent, particularly among women. Data also show that age and education play a role, higher migration rate at younger ages and higher levels of education.

Table 2 reveals that most people have migrated at some point in life. Nearly 40% of women and just over 50% of men have lived in their current location since birth. Among migrants, over 80% of both women and men moved within the same state. Migration patterns indicate a flow from rural areas to smaller towns and larger cities, with strong links between neighboring states. While men tend to migrate at younger ages, women are most likely to migrate between 18 and 24. Over 50% of both men and women who migrated have completed at least senior secondary education, suggesting education’s significant role in migration.

- Environment, Conflict, and Population Dynamics

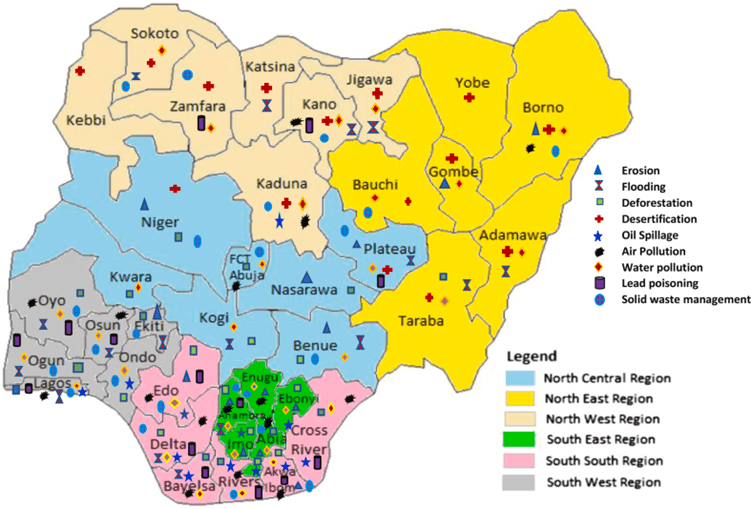

As more people migrate to urban areas, the growing industrialization of Nigerian cities has led to problems such as air pollution and water pollution, urban poverty, and desertification.[32]

Source: Pona, Hyellai Titus, Duan Xiaoli, Olusola O Ayantobo, and Daniel Tetteh Narh. “Environmental Health Situation in Nigeria: Current Status and Future Needs.” Heliyon 7, no. 3 (March 1, 2021)

These environmental issues directly impact citizens’ health and Nigerian lands while contributing to broader challenges. 31% of Nigeria’s forest loss is due to climate variability, threatening lands that provide nutrition to local communities.[33] Environmental pressures also fuel conflict between farmers and herders, not only in Nigeria but also in Mali and Burkina Faso, as shrinking arable land due to degradation encourages the rise of armed groups.[34]

Urban development and efforts to accelerate economic growth have side effects on poorer communities. Most oil extraction occurs in rural areas that local communities depend on, creating a trade-off between economic growth and rural living conditions.[35] As a result, environmental degradation is both a cause and a consequence in a vicious cycle driving many of Nigeria’s socio-economic problems.

Population-Related Policies

Nigeria’s first population policy, launched in 1988 as the Four is Enough campaign, aimed to limit childbearing in order to curb rapid population growth affecting national development and citizens’ welfare. However, its impact was limited. Between 1988 and 2004, the TFR only slightly decreased from 6.5 to 6.1. The policy had little influence in a culturally diverse, pronatalist society with a decentralized political structure.

The policy was revised in 2004 as the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development, expanding its focus to reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, and gender equity. However, progress remained slow: by 2013, TFR was 5.5, contraceptive use stagnated at 15%, and 44% of women were married before age 18. Weak implementation, poor infrastructure, and poverty undermined effectiveness. Infant mortality was 83 per 1,000 live births, and maternal mortality was 1,109 per 100,000. Nigeria’s participation in the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, supporting free contraceptive distribution, highlighted the gap between global frameworks and domestic implementation.[36]

The 2021 National Policy on Population revision focused on addressing the disconnect between population growth and GDP. Family planning was identified as a key strategy, with a target of reducing TFR below 3.0. The Federal Ministry of Health committed to FP2030, promoting informed reproductive choices and equitable access, but no funds from the health budget were allocated to family planning.[37] To support FP2030 goals, Nigeria implemented the National Family Planning Blueprint (2020–2024), aiming to raise modern contraceptive use to 27% and align with four goals: sustainable financing, scaling up high-impact practices, youth engagement, and integration into primary health care.[38]

The cumulative effect of policies is beginning to show modest progress. The UN Nigeria Annual Results Report 2024 shows that TFR dropped to 4.8, infant mortality fell from 98 in 2004 to 63 per 1,000 live births in 2024, and child marriage declined to 30%. Modern contraceptive use stands at 15.3% for married women and 38% for unmarried, sexually active women. However, unmet need for family planning among married women rose from 16.1% in 2013 to 21% by 2024, and only 37% report satisfaction with current methods.[39] Maternal mortality remains alarmingly high at 1,047 per 100,000 live births.[40]

Significant challenges remain, particularly regional and cultural disparities. Nigeria’s cultural complexity, home to over 250 linguistic groups, makes uniform policy implementation difficult. While macro-cultural values exist, localized micro-traditions shape reproductive behavior, reinforcing the need for context-sensitive approaches.

Current Policies (UN World Population Policies)

Nigeria’s approach to managing demographic trends and migration is guided by national policies with varying implementation success. The 2019 World Population Policies report notes that while no strategy exists to reduce rural-to-urban migration, decentralization is addressed through the 2012 National Urban Development Policy, promoting growth in smaller towns and suburban centers. There is no national policy for settling underpopulated areas, but relocation from environmentally fragile zones is carried out at the state level in response to climate threats like flooding or erosion.

Efforts to support rural development remain limited, with no formal policies to create jobs or move industries from urban to rural areas. However, the National Agricultural Investment Plan 2017–2020 improves market access for agricultural products and supports rural value chains. In parallel, the National Broadband Plan 2020–2025 includes measures to enhance digital infrastructure in rural areas, improving access to information and services.

In urban areas, Nigeria has introduced interventions to improve conditions for the urban poor, including policies to expand access to water, sanitation, education, and healthcare. However, housing remains a gap, with no comprehensive policy targeting low-income urban residents. A positive step is the 2017 National Social Protection Policy, which outlines strategies for vulnerable urban populations through cash transfers and access to services. On environmental sustainability, enforcement remains weak, with no national pollution limits, energy efficiency standards for buildings, or significant industry oversight. However, waste management and green space policies have been introduced at the city level, supported by national frameworks like the 2005 National Environmental Sanitation Policy.

The democratization in 1999 led to a series of advancements including the establishment of the UBE, and its related UBEC, which ensures that Nigerian children have access to 9 years of education.[41] Despite data showing that Nigeria still faces many challenges when it comes to education compared to other African states, already in 2010 the enrollment rate in schools for both young males and females was 80% as a consequence of UBE.[42] However, 10.2 million children do not have access to primary education and 8.1 million to secondary schools.[43]

Population and fertility-related measures have gained renewed emphasis under the 2022 revised National Policy on Population. Key objectives include increasing the age at first birth, promoting birth spacing, and raising the age of marriage or union formation. Adolescent fertility is of particular concern. Maternity leave is set at 180 days, but there is no provision for paternity or parental leave. Nigeria also lacks policies on childcare subsidies, flexible working hours for parents, or support for single-parent households.

Sexual and reproductive health has seen some policy progress. The 2003 Child Rights Act sets the legal marriage age at 18, but by 2016, only 24 states had adopted it. The 2015 Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act criminalizes forced marriage, domestic and sexual violence, and female genital mutilation, though implementation is in just 13 states. The 2017 National Reproductive Health Policy ensures access to maternal care, family planning, and sexual education. Contraceptive services are available without restrictions, and abortion is legal only to preserve a woman’s health, with no allowance for rape or economic hardship. HIV/AIDS interventions focus on high-risk groups, with no age or marital status restrictions for testing and care.

Policy proposals

To convert Nigeria’s growing working-age population into a demographic dividend, coordinated investments in health, education, and employment are crucial. The Asian Tigers’ experience shows that fertility and mortality decline must be accompanied by family planning, educational expansion and labor market reforms. In Nigeria, high child mortality and fertility rates remain key barriers, and without strategic policy action, the demographic transition cannot yield benefits.

Healthcare

The “Three Delays Model” by Gina Piane outlines key barriers Nigerian women face during childbirth. Nigeria accounts for 28.3% of global maternal deaths, with only 43% of births attended by skilled providers and 59% occurring at home.[44] Based on current population projections, Nigeria would need approximately 409,332 doctors by 2027 to meet WHO recommendations, yet it currently has only around 24,600.[45] Reducing maternal mortality heavily depends on access to skilled healthcare, requiring the government to invest strategically and collaborate with NGOs. Expanding healthcare involves building and equipping facilities, especially in rural areas, and recruiting qualified personnel. Strengthening maternal and childcare must become a national priority, with state and local governments ensuring consistent funding for primary healthcare as part of Universal Health Coverage.[46]

Lowering fertility proves equally crucial to achieve a demographic transition. One in four Nigerian women wants to delay or avoid pregnancy but lacks access to modern contraception.[47] Expanding access to family planning and reproductive health services is essential for population management and national development. Educating individuals and ensuring access to services will enable families to plan their pregnancies more effectively, leading to smaller and healthier families.

Policymakers must recognize the link between family planning and socio-economic stability. As public discourse ties rapid population growth to insecurity, discussions should foster a national consensus on the role of population policy in achieving development goals. Collaborating with think tanks, educational institutions, and public platforms can align values with evidence-based strategies for sustainable growth.

Investing in maternal and child health strengthens the foundation for a demographic dividend, as improved child survival reduces fertility. A strong health system and targeted programs are essential. Addressing cultural norms, like the Abiku mythology, requires community education and awareness campaigns. These grassroots efforts are crucial for long-term change, and the government should launch a national campaign to promote the National Population Policy, aligning population trends with social and economic policies.

Socio-economic

Nigeria is positioned to benefit from the first demographic dividend as its working-age population grows. To capitalize on this opportunity, timely policy action is essential. The education system must evolve to meet the needs of a growing school-age population, ensuring equal access for boys and girls. Emphasizing secondary education for girls is crucial to delaying early marriage and reducing adolescent pregnancies. Strengthening the legal framework to address early, forced, and child marriage is key to improving educational and health outcomes for girls. By 2027, maintaining a reasonable pupil-teacher ratio will require approximately 6.46 million teachers – 300,000 more than today – and at least 20,000 new schools.[48] Policymakers must prioritize investment in school infrastructure and teacher training, especially in underserved areas.

A supportive economic environment must include policies that align with market demands and absorb the expanding labor force. To this end, vocational and technical training should prepare young workers for both labor-intensive sectors and advanced roles in agriculture, business, and technology. An urgent national program to retrain public servants in population planning and human capital development is essential to drive these efforts.

As fertility declines and families have fewer dependents, household income rises, creating opportunities for savings and investment. Institutional readiness is essential, particularly in strengthening legal frameworks like contract law and financial regulation to encourage investment. A stable macroeconomic environment with low inflation and transparency will stimulate domestic savings and private investment, laying the groundwork for the second demographic dividend as the population ages and savings accumulate. Policies promoting financial security and labor market access for older adults are needed to prepare for this transition.

Good governance is critical throughout this process. Reducing corruption, enhancing institutional efficiency, and promoting gender equality will drive both governance priorities and demographic-economic development. Under the Renewed Hope Agenda, the government’s focus on youth employment, the digital and creative economy, and empowering women is a vital step forward.[49] The domestication of the National Women Economic Empowerment Policy is crucial, addressing poverty and deprivation faced by women and children and fostering a more equitable society.[50] With the right policies across education, labor, financial systems, and governance, Nigeria can turn its demographic window into sustained economic growth.

Urban Migration and Environment

Migration and environmental issues are closely linked. Many people migrate to urban areas, contributing to pollution, while environmental degradation forces others to move. In both cases, the government must act urgently to prevent conflicts, such as the farmer-herder clashes, from escalating. According to the 2019 UN World Population Policies, Nigeria lacks policies to regulate pollution and industrial emissions, as well as measures to curb rural-to-urban migration and promote rural development.

Nigerian authorities should prioritize rural areas over urban development. Investing in rural infrastructure and relocating some industries from urban to rural areas would create jobs and secondary schools, reducing migration and easing urban overcrowding and environmental strain. However, rural development must avoid past strategies that led to conflicts and demonstrated a lack of political will. Creating opportunities for youth to study and work without leaving their land must not disrupt local communities, as seen with the River Benue, which served agriculture, transport, fishing, block industry, and rice milling from 1960 to 2020.[51]

Policymakers must reconsider social protection policies for vulnerable Nigerians, adopting evidence-based approaches to target the poorest and most at-risk populations. Poverty reduction programs should prioritize specific groups, such as the rural poor, those in chronic poverty, and female-headed households. Data-driven decisions should guide these efforts. Additionally, thorough studies on the impact of poverty reduction programs must be conducted and shared to rebuild trust in social protection initiatives and ensure they deliver real results for those in need.

Conclusions

The population dynamics in Nigeria are shaped by a unique blend of socio-cultural, economic, and environmental factors. As the country faces challenges such as rapid urbanization, high fertility rates, and socio-economic inequalities, addressing these issues requires a multi-dimensional policy response. Education, healthcare, and economic reforms are essential to leverage Nigeria’s growing working-age population and achieve a demographic dividend. The importance of family planning improved maternal healthcare, and the reduction of early marriages must be emphasized in policy discussions.

In addition, tackling gender disparities, particularly through investments in girls’ education and empowering women, is vital for long-term development. The ongoing struggle between traditional beliefs and modern policies underscores the complexity of demographic transitions. Policymakers need to carefully balance cultural beliefs with evidence-based solutions, integrating cultural sensitivity into development strategies. A clear emphasis on rural development, supported by improved infrastructure and localized job creation, will ease migration pressures and contribute to environmental sustainability. Furthermore, the alignment of governance priorities with inclusive policies and institutional reforms will strengthen Nigeria’s ability to transform its demographic potential into sustainable growth. International collaboration will play a crucial role in supporting Nigeria’s development efforts. To conclude, a holistic approach, combining both energy and socio-economic development initiatives, will be essential in addressing Nigeria’s demographic challenges and creating sustainable growth.

[1]Worldometer, “Nigeria Population (2025),” https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nigeria-population/

[2] Our World in Data, “Population Growth Rate,” https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/population-growth-rates?country=~NGA

[3] Graf, William D, “The Nigerian New Year’s Coup of December 31, 1983: A Class Analysis,” Journal of Black Studies 16, no. 1 (1985): 21–45.

[4] Our World in Data, “Population Growth Rate,” https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/population-growth-rates?country=~NGA

[5]Monica Ewomazino Akokuwebe and Rasidi Okunola, “Demographic Transition and Rural Development in Nigeria,” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292140956_Demographic_Transition_and_Rural_Development_in_Nigeria

[6]Musa Abdullahi Sakanko, “An Econometric Validation of Malthusian Theory: Evidence in Nigeria,” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322763348_An_Econometric_Validation_of_Malthusian_Theory_Evidence_in_Nigeria

[7]Etebong Peter Clement, “Demography in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects,” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326540602_Demography_in_Nigeria_Problems_and_Prospects

[8]World Bank Open Data, “World Bank Open Data,” https://data.worldbank.org

[9] Bloom, David E., and Jeffrey G. Williamson, “Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia,” The World Bank Economic Review 12, no. 3 (September 1, 1998): 419–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/12.3.419

[10] We recall that, throughout the paper, when it comes to international comparison, we selected specifically five countries for a combination of reasons. Sub-Saharan Africa was chosen due to its economic and demographic similarities, offering relevant comparisons for a region with similar developmental challenges. The Middle East & North Africa was included to compare regions with varying socio-economic contexts, while OECD members were selected to represent higher income, developed economies with more advanced infrastructure and policy frameworks. Lastly, the World sample provides a broader, global perspective to contextualize Nigeria’s data within a wider international framework. These regions were chosen to balance proximity in terms of development and economic indicators while also providing diversity in socio-economic conditions.

[11] Lee, K. S., S. C. Park, B. Khoshnood, H. L. Hsieh, and R. Mittendorf, “Human Development Index as a Predictor of Infant and Maternal Mortality Rates,” The Journal of Pediatrics 131, no. 3 (September 1997): 430–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80070-4

[12]UNDP, “Valuable Insights and Findings of the 2023/2024 Human Development Report and Its Correlation to Nigeria’s Human Development Index,” https://www.undp.org/nigeria/news/valuable-insights-and-findings-2023/2024-human-development-report-and-its-correlation-nigerias-human-development-index

[13] ibidem

[14]Siddharth Dixit et al., Nigeria’s Health Transitions: Country Impact Profile, Center for Policy Impact in Global Health, March 2022, https://centerforpolicyimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2022/03/Nigeria-4Ds-Country-Profile-Final.pdf

[15]Piane, Gina Marie, “Maternal Mortality in Nigeria: A Literature Review,” World Medical & Health Policy 11, no. 1 (2019): 83–94, https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.291

[16] Ogunjuyigbe, Peter Olasupo, “Under-Five Mortality in Nigeria: Perception and Attitudes of the Yorubas Towards the Existence of ‘Abiku,” Demographic Research 11 (August 13, 2004): 43–56, https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2004.11.2

[17] Smith, Daniel Jordan, “Contradictions in Nigeria’s Fertility Transition: The Burdens and Benefits of Having People,” Population and Development Review 30, no. 2 (2004): 221–38

[18] “UN Nigeria Annual Results Report 2024 | United Nations in Nigeria.” https://nigeria.un.org/en/292111-un-nigeria-annual-results-report-2024

[19] ibidem

[20] Smith, Daniel Jordan, “Masculinity, Money, and the Postponement of Parenthood in Nigeria,” Population and Development Review 46, no. 1 (March 2020): 101–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12310

[21] Bolarinwa, Obasanjo Afolabi, Bright Opoku Ahinkorah, Abdul-Aziz Seidu, Aliu Mohammed, Fortune Benjamin Effiong, John Elvis Hagan, and Olusesan Ayodeji Makinde, “Predictors of Young Maternal Age at First Birth among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria,” PLOS ONE 18, no. 1 (January 13, 2023): e0279404 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279404

[22] Mberu, Blessing Uchenna, “Household Structure and Living Conditions in Nigeria,” Journal of Marriage and Family 69, no. 2 (2007): 513–27

[23] Boyle, Elizabeth Heger, and Joseph Svec, “Intergenerational Transmission of Female Genital Cutting: Community and Marriage Dynamics,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 81, no. 3 (June 2019): 631–47

[24] Olowolafe, Tubosun A., Ayo S. Adebowale, Adeniyi F. Fagbamigbe, Obiageli C. Onwusaka, Nicholas Aderinto, David B. Olawade, and Ojima Z. Wada, “Decomposing the Effect of Women’s Educational Status on Fertility across the Six Geo-Political Zones in Nigeria: 2003–2018,” BMC Women’s Health 25, no. 1 (March 8, 2025): 107, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03636-z

[25] Filippo Grandi [@FilippoGrandi], “I Was in Chad. I Saw Sudanese Refugees Arriving, Fleeing Violence in Darfur. Unless Efforts to Bring the Parties to the Sudan Conflict to the Negotiating Table Become Serious, the Humanitarian Crisis Will Keep Growing – as Resources to Support the Response Continue to Decline. Https://T.Co/dh7jw7mORL,” Tweet. Twitter, April 11, 2025, https://x.com/FilippoGrandi/status/1910791787037561293

[26]International Organization for Migration (IOM), Internal Migration Trends in Nigeria, May 2024, https://nigeria.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1856/files/documents/2024-05/internal-migration-trends-in-nigeria.pdf

[27] ibidem

[28]Abubakar, Ahmad Said, Nura Isyaku Bello, and Auwal Haruna Ismail, “Navigating Environmental Migration in Nigeria: Trends, Impacts, And Strategic Responses” 8 (2025).

[29] International Organization for Migration (IOM), Migration in Nigeria: A Country Profile 2019, 2019, https://nigeria.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1856/files/documents/2024-04/the-national-migration-profile-2019_0.pdf.[30] Mberu, Blessing U, “Who Moves and Who Stays? Rural out-Migration in Nigeria,” Journal of Population Research 22″, no. 2 (September 1, 2005): 141–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031826

[31] Amare, Mulubrhan, Kibrom A. Abay, Channing Arndt, and Bekele Shiferaw, “Youth Migration Decisions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Satellite-Based Empirical Evidence from Nigeria,” Population and Development Review 47, no. 1 (2021): 151–79, https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12383

[32]Pona, Hyellai Titus, Duan Xiaoli, Olusola O. Ayantobo, and Narh Daniel Tetteh, “Environmental Health Situation in Nigeria: Current Status and Future Needs,” Heliyon 7, no. 3 (March 23, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06330

[33] Khan, Bhoktear, Piyush Mehta, Dongyang Wei, Hanan Abou Ali, Oluseun Adeluyi, Tunrayo Alabi, Olawale Olayide, John Uponi, and Kyle Frankel Davis, “Cropland Expansion Links Climate Extremes and Diets in Nigeria,” Science Advances 11, no. 2 (January 10, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado5541

[34]Brottem, Leif, “The Growing Complexity of Farmer-Herder Conflict in West and Central Africa,” Africa Center (blog), https://africacenter.org/publication/growing-complexity-farmer-herder-conflict-west-central-africa/

[35]Taiwo, Akinlo, “Environmental Degradation on Poverty Reduction in Nigeria,” Journal of Social and Economic Development, June 14, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-024-00348-2

[36] Renne, Elisha P, “Interpreting Population Policy in Nigeria,” In Reproductive States: Global Perspectives on the Invention and Implementation of Population Policy, edited by Rickie Solinger and Mie Nakachi, 0. Oxford University Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199311071.003.0009

[37] development Research and Projects Centre (dRPC), National Population Policy and Family Planning, August 2022, https://drpcngr.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NATIONAL-POPULATION-POLICY-AND-FAMILY-PLANNING.pdf

[38]Family Planning 2030, “North, West and Central Africa,” https://www.fp2030.org/regional-hubs/north-west-and-central-africa/

[39] Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Nigeria (FMoHSW), National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], and ICF, Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2023–24: Key Indicators Report (Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, MD: NPC and ICF, 2024), https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR157/PR157.pdf

[40] Gabriel Dogbanya, “Maternal Mortality in Nigeria: Holding the Line in Uncertain Times,” Annals of Global Health 91, no. 1 (2025): 1–2, https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4710

[41] Education Policy Data Center. “EPDC Spotlight on Nigeria,” October 31, 2014. https://www.epdc.org/epdc-data-points/epdc-spotlight-nigeria

[42] ibidem

[43] “UN Nigeria Annual Results Report 2024 | United Nations in Nigeria.” https://nigeria.un.org/en/292111-un-nigeria-annual-results-report-2024

[44] Gabriel Dogbanya, “Maternal Mortality in Nigeria: Holding the Line in Uncertain Times,” Annals of Global Health 91, no. 1 (2025): 1–2, https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4710

[45] World Health Organization, Country Cooperation Strategy 2023–2027: Nigeria. Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2024, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378243/9789290343363-eng.pdf

[46] Ilesanmi, Olayinka Stephen, Aanuoluwapo Adeyimika Afolabi, and Christianah Toluwalope Adeoya, “Driving the Implementation of the National Health Act of Nigeria to Improve the Health of Her Population,” The Pan African Medical Journal 45 (2023): 157, https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2023.45.157.37223

[47] Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Nigeria (FMoHSW), National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], and ICF, Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2023–24: Key Indicators Report (Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, MD: NPC and ICF, 2024), https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR157/PR157.pdf

[48] World Bank Open Data, “World Bank Open Data,” https://data.worldbank.org.

[49] All Progressives Congress (APC), Renewed Hope 2023: Action Plan for a Better Nigeria, 2023, https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2023/02/RENEWED-HOPE_compressed.pdf

[50] Federal Ministry of Women Affairs (Nigeria), National Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) Policy and Action Plan, May 2023, https://youngafricanpolicyresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/WEE-POLICY-AND-ACTION-PLAN.pdf

[51] Igba, David M, and Thaddeus T Ityonzughul. “Ocean Economy in Nigeria: Analysis of the Economic Benefits of River Benue,” 2023.