Abstract

The war between Russia and Ukraine has profoundly reshaped the European Union’s energy security strategies, transforming energy from a technical and economic concern into a cornerstone of regional stability and resilience. This analysis explores the strategic responses adopted by the European Union through militarization of infrastructure, the expansion of energy diplomacy, and the promotion of decentralized energy systems. Several military measures have been adopted to safeguard energy assets, not only by incorporating energy security into defense networks, but also by strengthening NATO cooperation. Underscoring the importance of diversification among energy partners, together with the imposition of sanctions on Russia, the role of diversified energy systems has become pivotal in enhancing resilience in energy generation and storage. The prominent need to balance geopolitical challenges with internal EU divergences underscores how the EU is redefining its energy security to navigate contemporary geopolitical crises.

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 marked a watershed moment in contemporary geopolitics, reigniting tensions in Europe and challenging the stability of the international order.[1] Beyond the imminent humanitarian crisis, the war had repercussions over economic, political, and security domains, exposing all the vulnerabilities countries had accumulated over the previous decades. The most relevant vulnerability is exemplified by “energy security”, which quickly became both a weapon and a victim of the conflict. Russia leveraging its role as one of the world’s largest energy exporters, used gas exports as a tool for political coercion, cutting supplies to European countries as a retaliation for sanctions and military support to Ukraine. The European Union, which had long relied on affordable and abundant Russian oil and gas to fuel its economies, was forced to face the risks of energy dependency vis-à-vis a hostile actor in the context of geopolitical conflicts. Several events, such as the sabotage of the Nord Stream Pipeline, highlighted an advanced degree of intersection between energy systems and national security. For instance, a head-to-toe reorientation and redefinition of energy diplomacy moved at the top of any agenda.[2] To understand the impact provoked by the Russia-Ukraine war over energy security and energy diplomacy it becomes necessary to investigate three main aspects:

- The militarization of energy infrastructure, focusing on the deployment of military resources to safeguard critical assets and the integration of energy security into defense policies.

- Energy diplomacy as a tool for diversifying energy supplies and countering the weaponization of energy.

- How decentralized energy systems act as an alternative to traditional technologies.

By addressing these three dimensions the European Union has adapted its energy security to one of the most significant geopolitical crises of the XXI century.

The Militarization of Energy Infrastructure: A Strategic Shift in EU Security Policy

Energy infrastructure was primarily perceived as an economic asset; however, the past three years gradually conceived them in a broader scope of economic stability and regional security.[3] The growing military involvement in safeguarding critical energy assets and a broader integration of energy security into the European Union demonstrate the attempt to redefine the approach to this domain, which is not merely an economic necessity but also a strategic priority for the European Union.

Sabotages and hybrid threats need to be addressed through the deployment of military forces to safeguard vital energy assets, the establishment of rapid-response units to address energy-related crises, and a well-structured cooperation with NATO to integrate infrastructure protection into a broader security framework. As strategy infrastructure becomes an increasingly prominent target for hybrid warfare, the European Union has encouraged its member states to adopt stronger protective measures.[4] The sabotage of the Nord Stream Pipeline in September 2022 unveiled the vulnerability of undersea and land-based energy infrastructure, resulting in EU Commission directives urging member states to bolster physical security at critical energy facilities.[5] For example, Norway (an EU-adjacent country and key natural gas supplier to the region) expanded military patrols around offshore platforms and pipelines.[6] Also, Germany increased military presence near LNG terminals such as the Brunsbüttel facility, deploying naval and air patrols to monitor for potential threats.[7] Security controls cannot be limited to naval and land manpower, but they must be implemented through new technologies: this was the case of satellite systems. For instance, according to the European Space Agency, the Copernicus satellite, using the Sentinel-1 system, has been crucial in detecting anomalies in undersea pipelines and monitoring energy facilities in remote regions.[8] Furthermore, since 2023, France has announced an increasing deployment of specialized gendarmerie units to protect nuclear power plants from potential sabotage attempts.[9] As Le Monde reports, French Intelligence agencies have acknowledged the risks of physical and cyber intrusions targeting energy facilities and bolstering military deployments has become the bare minimum to ensure the uninterrupted operation of energy assets.[10]

As Margrethe Vestager – former executive vice president of the European Commission – affirms, security, to be effective, cannot be delimited to prevention, but it also requires a solid resilient structure.[11] The establishment of rapid-response military units tailored to energy crises has been a hot topic in the agendas of EU Member States for the past three years, resulting in the creation of units designed to respond swiftly to incidents resulting from sabotages, natural disasters, or any other disrupting cause. As a matter of fact, the European Defense Fund (EDF), expanded in 2021, now allocates funding for the development of rapid-response actions.[12] An example could be the case of Lithuania, a frontline state in the EU’s energy security landscape, which established specialized military units in collaboration with the EDF to protect its electricity interconnector with Poland, known as “LitPol Link”.[13] According to Bloomberg, Italy has also developed a rapid-response naval unit to protect undersea pipelines connecting North Africa to Europe.[14] The well-known Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline has been designated by NATO as a critical infrastructure due to the crucial role that it plays in supplying natural gas from Algeria to Italy.[15] TransMed security has been a top priority of Italy’s Ministry of Defense which deployed a naval task force to monitor the pipeline’s offshore segments.[16]

The deployments of military forces and the establishment of rapid-response units must be envisioned within a broader scenario of cooperation between the European Union and NATO. For instance, the EU-NATO Task Force on Resilience of Critical Infrastructure, established in 2023, provides a platform for joint analysis and policy alignment.[17] However, the EU is willing to strengthen its autonomous capabilities through the Critical Energy Infrastructure Directive (2023) which mandates member states to conduct risk assessments and implement security upgrades for energy facilities.[18] This cooperation goes beyond theoretical aspirations, and it find its concrete application in the Operation Baltic Shield, a joint EU-NATO initiative launched in 2023 to protect energy infrastructure in the Baltic Region.[19] According to the European Defense Agency, the European Union would support NATO military assets with EU-funded surveillance drones to monitor undersea pipelines and power cables, underscoring the EU’s leadership in leveraging advanced technologies for energy security.

Building on military initiatives, the European Union has recognized that securing energy systems requires not only physical protection, but also a deeper integration of energy security into its defense policies. It is evident that the vulnerabilities exposed by the Russia-Ukraine war forced the European Union into incorporating energy security scenarios in their foreign policy planning. According to the European Commission’s Strategic Foresight Report 2023, energy disruptions are now officially integrated into the Strategic Compass for Security and Defense, adopted since March 2022.[20] [21] The immediate consequence has been the inclusion of energy-related scenarios in the EU member states’ military exercises; for example, in 2023, the EU conducted a joint exercise in Riga, “Coherent Resilience 2023 Baltic”, involving member states’ armed forces and energy stakeholders, where they simulated coordinated attacks on critical infrastructure, such as LNG terminals and power grids, to test both military response and civilian resilience.[22]

The aforementioned hybrid threats, which combine physical, cyber, and disinformation tactics, require hybrid defense strategies.[23] Therefore, the European Union has responded by promoting integrated defense approaches that address these multifaceted risks; for example, the Cybersecurity Strategy for the Energy Sector, released by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) in 2023.[24] [25] More specifically, countries like Germany have developed their own cyber defense system: the Kommando Cyber und Informationsraum, already operational since 2017.[26] Following repeated cyberattacks on its energy grid between 2022 and 2023, Germany has expanded its hybrid defense targeting energy infrastructure as a priority area, and involving close collaboration with the Bundeswehr, private energy operators, and EU agencies to develop rapid-response teams that can address cyber and physical threats in real-time.[27]

Energy Diplomacy as a Pillar of European Security: Strategic Diversification and Resilience in a Post Russia-Ukraine War Era

The weaponization of energy infrastructures has clearly highlighted the need to diversify the EU energy portfolio, leaving space for a new topic to be discussed in diplomatic venues. Energy diplomacy goes even further mere partnership diversification, which must be combined with a robust internal strategy to counter energy coercion. Together, these initiatives underscore the EU’s commitment to leveraging energy diplomacy not only as an economic tool, but also as an instrument to maintain collective stability and security.

The European Union’s pursuit of energy security has driven it to establish strategic partnerships with key global suppliers. Besides the future challenges which the EU might face during the next four years of Trump Administration, the United States has emerged as the main LNG supplier to the European Union. Following the reduction of Russian gas imports, the United States accounted for 26% of all LNG imported by the European Union member states, becoming Europe’s largest supplier.[28] This trend continued with the United States maintaining their position as the largest exporter of LNG until 2024, with record shipments of 56.9 million metric tons during the first eight months.[29] Similarly to the USA, Qatar has also acted as a major partner having the third largest natural gas possession on the planet. Based on information provided by the USA Energy Information Administration, in 2022 Qatar accounted for 24% of Europe’s total LNG imports, representing one of the EU’s major gas suppliers since the breakout of the conflict.[30] Lastly, Algeria remains an historical energy partner for the European Union, supplying natural gas through both pipelines and LNG shipments. The TransMed pipeline, for instance, delivers Algerian gas directly to Italy, and, in the first half of 2024, Algeria accounted for 11% of Europe’s LNG imports, demonstrating its importance in the EU’s energy diversification strategy.[31] However, as much as in several other occasions, the EU lacks a cohesive strategy to address the energy security challenge, reflecting, once again, the interests of national agendas over collective interests.

Alongside traditional energy suppliers, other countries have carved their path in the list of European Union’s suppliers. It’s the case of Norway which took the stand establishing itself as one of the primary natural gas suppliers in 2024, accounting for approximately 30% of the European Union’s gas imports, with projections indicating that these elevated levels will persist in the coming years.[32] [33] The Troll Field, a cornerstone of Norway’s gas production, achieved a 42.5 billion standard cubic meters production of gas in 2024, underscoring the weight that this supplier has had over EU energy security.[34] This cooperation goes beyond mere gas supplies, and the EU has further reinforced this relationship formally signing the EU-Norway Energy Dialogue, focusing on both immediate and long-term energy supplies and advancing common initiatives on renewable energy, carbon capture, and storage solutions.[35] Similarly, the EU is pursuing dialogues with Israel, Cyprus, and Greece to exploit offshore gas reserves.[36] An emblematic example in this field is the EastMed Pipeline project, a 1900 kilometers structure designed to transport gas from East Mediterranean fields to Europe, via Greece. Traveling across several countries, the EastMed Pipeline will necessarily need to fit into different agendas and some doubts arise about the feasibility of the project.[37] However, the European Union seems to be particularly interested in fostering, besides this specific project, a concrete East Mediterranean cross-country collaboration. For instance, this cooperation finds its diplomatic application in the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), gathering countries such as Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, and Italy which have already accomplished great achievements.[38] A remarkable one is the trilateral agreement signed in 2022 between the EU, Egypt, and Israel, which facilitates the export of Israeli natural gas to Europe via Egypt, where the gas is liquefied and transported to European markets.[39]

Decentralized Energy Systems as a Framework for Enhanced Energy Security: Conclusions and Recommendations

Concrete solutions must be adopted to enhance security in energy infrastructures and decentralized energy systems represent a pillar within this framework. These systems do not only offer a robust resilience structure, but they also leverage resources to address and supply stability aiming for broader EU goals in terms of energy independence. Decentralized energy systems, through the promotion of local energy generation and storage solutions and the creation of secure and smart grids, offer a valid alternative to the EU energy future.

Community energy projects and microgrids have demonstrated how smaller regions can produce and manage their energy, thereby reducing reliance on centralized power grids and fostering resilience against any kind of disruption. These localized systems can exploit multiple renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, adjusted to the specific resources and needs of the community, as has been done with the TILOS project on Tilos Island, in Greece.[40] Another prominent example, financed by the European Union, is ALPGRIDS, which focuses on constructing microgrids based on renewable resources in Alpine regions energy sources, allowing communities to generate and consume energy locally.[41]

Evidently, both these projects need financial incentives to local communities and individual households to transition toward renewable installations: for this reason the European Commission has approved a 5.7 billion euros Italian State aid program under the Recovery and Resilience Facility.[42] [43] Subsidies might not be enough if the EU does not implement regulatory frameworks to incentivize generation among businesses and households. To ensure the feasibility of these projects, it becomes imperative that all policies are transparent, non-discriminatory, and cost-effective.[44] Indeed, exemptions exist, for example for small-scale installations due to the unique challenges that they might face. For this reason, the Renewable Energy Directive obliges EU countries to allocate support for electricity from renewable sources in a manner that encourages participation from small-scale producers, so promoting a more decentralized and resilient energy system.[45]

Once these systems have been conceived, they also require a structured plan to ensure their stability. Empowering communities to produce their own energy clearly enhances resilience, however, the variability of renewable energy sources like wind and solar, necessitates solid storage solutions to ensure a steady energy supply. Three main strategies have been fostered by the EU: large scale investments in storage technologies, incorporation of storage projects into funding programs like Horizon Europe, and priority over long-duration storage solutions. Large scale investments for storage technologies are the milestone of this resilience project, due to the EU Commission efforts to enhance battery development across member nations.[46] [47] These investments find their concrete application in the Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners’ 800 million pounds commitment to build large-scale battery storage systems in Scotland.[48] This project, which would collectively support 4.5 million households for two hours, as much as many other EU initiatives, demonstrate the willingness to advance large-scale and durable energy storage projects.[49]

Once again, all these technological advancements need solid and strengthened EU policies for managing decentralized energy systems during emergencies.[50] The Digitalization of Energy Action Plan outlines measures to ensure a sustainable, cyber-secure, transparent, and competitive market for digital energy services.[51] This includes the establishment of the Smart Energy Expert Group, which assists the Commission on issues regarding the sustainable digital transformation of the energy system and the development and deployment of smart energy solutions that support the goals of the green digital transition.[52] To conclude, these initiatives underscore the EU commitment to creating secure and smart decentralized grids. By integrating AI-driven digital energy systems, implementing blockchain-based security measures, and reinforcing policies for emergency management, the European Union aims to enhance energy security, promote sustainability, and ensure resilience when facing emerging challenges.

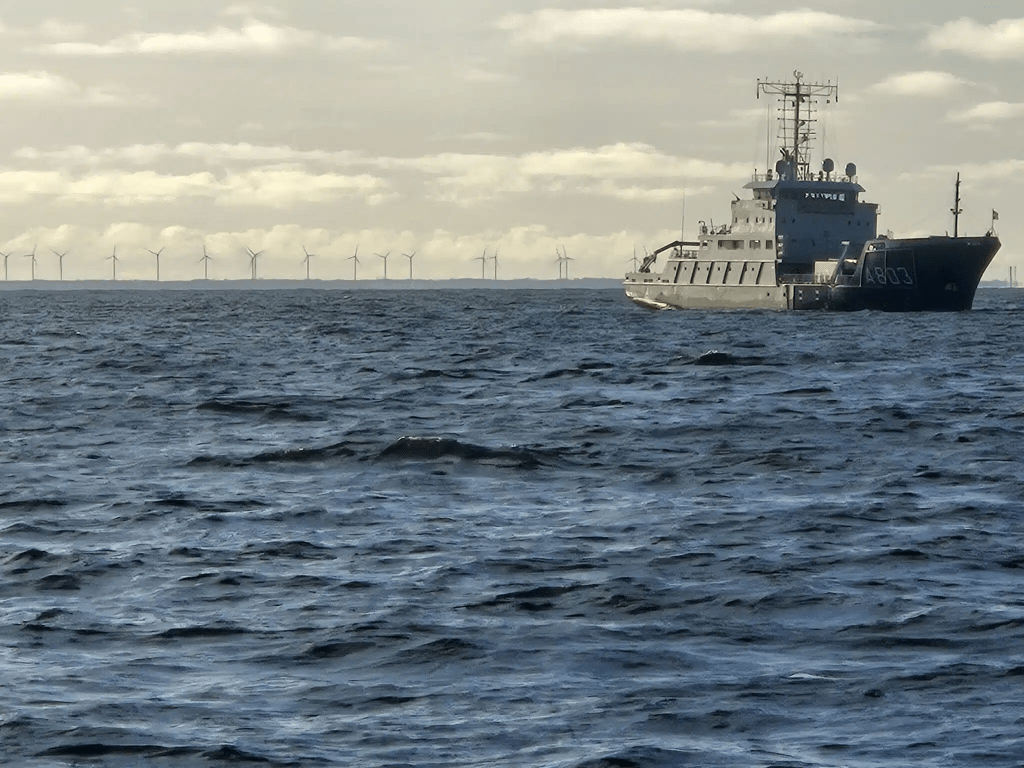

Cover image: Energy Union / © 2015 European Union

[1] Marc Finaud, Russia-Ukraine War: Implications for the Future of Armed Conflict (Geneva: Geneva Centre for Security Policy, 2023), https://dam.gcsp.ch/files/doc/gcsp-analysis-russia-ukraine-war-implications.

[2] Avi Schnurr, Beyond the Grid: The Case for Decentralized Energy Systems, Electric Infrastructure Security (EIS) Council, 2023, https://eiscouncil.org/beyond-the-grid-the-case-for-decentralized-energy-systems/.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] European Commission, Annual Progress Report 2024, Staff Working Document, pages 8–9, accessed January 11, 2025, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2025-01/SWD_Annual-Progress-Report-2024.PDF.

[5] Security Council Report, “The Nord Stream Incident: Open Briefing,” What’s in Blue, October 2024, accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2024/10/the-nord-stream-incident-open-briefing.php.

[6] Captain, “Norway Stepping Up Patrols of Oil and Gas Platforms with Help from Allies,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/norway-stepping-up-patrols-of-oil-and-gas-platforms-with-help-from-allies/.

[7] European Commission, State Aid SA.102163 (2024): Decision Document, accessed January 11, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/202412/SA_102163_804D418E-0000-CBFB-B3DB-44C96A1FD7F3_127_1.pdf.

[8] Copernicus, The Danish Climate Atlas (Copenhagen: Danish Meteorological Institute, n.d.), 106–128, https://www.klimadatastyrelsen.dk/media/6611/copernicus-eng_digital.pdf.

[9] Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire (IRSN), Safety of Nuclear Power Plants, sections 1.3, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.6.3, accessed January 11, 2025, https://en.irsn.fr/sites/en/files/2023-09/SNP_english_WEB.pdf.

[10] Le Monde, “French Military Intelligence Is Worried about Increasing Foreign Interference,” Le Monde, July 15, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/france/article/2024/07/15/french-military-intelligence-is-worried-about-increasing-foreign-interference_6684510_7.html.

[11] European Commission, “Remarques de la Commission sur la stratégie de sécurité économique,” Press Corner, June 20, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/fr/speech_23_3388.

[12] European Commission, “European Defence Fund (EDF): Official Webpage,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/european-defence-fund-edf-official-webpage-european-commission_en.

[13] Euronews, “Lithuania Ramps Up Power Grid Security Ahead of Russia Decoupling,” January 9, 2025, accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/01/09/lithuania-ramps-up-power-grid-security-ahead-of-russia-decoupling.

[14] Bloomberg, “Italy to Deploy Navy to Tighten Protection of Gas Pipelines,” September 30, 2022, accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-30/italy-to-deploy-navy-to-tighten-protection-of-gas-pipelines.

[15] NATO Maritime Command, “NATO Ships Cooperate with Italian Navy to Monitor Critical Undersea Gas Pipelines in the Adriatic Sea,” NATO, February 2, 2024, https://mc.nato.int/media-centre/news/2024/nato-ships-cooperate-with-italian-navy-to-monitor-critical-undersea-gas-pipelines-in-the-adriatic-sea.

[16] Alessandro Marrone and Eleonora Ardemagni, The Protection of Critical Energy Infrastructures: The Role of Armed Forces (Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2023), 25, https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/iairp_24.pdf.

[17] European Commission, EU-NATO Final Assessment Report on Digital Cooperation, June 2023, accessed January 11, 2025, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/EU-NATO_Final%20Assessment%20Report%20Digital.pdf.

[18] European Union, Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the Resilience of Critical Entities, Official Journal of the European Union, L 333/164, December 27, 2022, accessed January 11, 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2557/oj.

[19] Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “NATO Baltic Sea Security: Nord Stream and Balticconnector,” May 2024, accessed January 11, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/05/nato-baltic-sea-security-nord-stream-balticconnector?lang=en.

[20] European External Action Service, “Strategic Compass for Security and Defence,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/strategic-compass-security-and-defence-1_en.

[21] European Commission, Strategic Foresight Report 2023: Charting the Course for a Resilient Europe, July 2023, accessed January 11, 2025, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-07/SFR-23-beautified-version_en_0.pdf.

[22] European Commission, “Strengthening European Resilience in Critical Infrastructure Protection,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/cipr/items/823874/.

[23] NATO, “Energy Security,” NATO, last updated March 15, 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/on/natohq/topics_156338.htm.

[24] European Parliament, Energy Security in the EU: The Role of Russia, Briefing, December 2017, accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2017/602019/IPOL_ATA(2017)602019_EN.pdf.

[25] European Union, “European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA),” accessed January 11, 2025, https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/institutions-and-bodies/search-all-eu-institutions-and-bodies/european-union-agency-cybersecurity-enisa_en.

[26] Bundeswehr, “Kommando Cyber- und Informationsraum,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.bundeswehr.de/de/organisation/cyber-und-informationsraum/kommando-und-organisation-cir/kommando-cyber-und-informationsraum.

[27] DW, “Germany Launches Military Reform with New Command Structure,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-launches-military-reform-with-new-command-structure/a-68740863.

[28] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “U.S. Natural Gas Pipeline Exports to Mexico Set a Monthly Record in June 2021,” accessed January 12, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=51358.

[29] Reuters, “U.S. LNG Export Dominance Tested as Europe’s Demand Wilts: Maguire,” September 4, 2024, accessed January 12, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/us-lng-export-dominance-tested-europes-demand-wilts-maguire-2024-09-04/.

[30] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “U.S. Natural Gas Pipeline Exports to Mexico Set a Monthly Record in June 2021,” accessed January 12, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=51358.

[31] Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, “European LNG Tracker: September 2024 Update,” accessed January 12, 2025, https://ieefa.org/european-lng-tracker-september-2024-update.

[32] “Norway Sets Record for Gas Exports in 2024, Retains Position as Europe’s Top Supplier,” Cord Magazine, accessed January 13, 2025, https://cordmagazine.com/world-news/norway-sets-record-for-gas-exports-in-2024-retains-position-as-europes-top-supplier/.

[33] “Norway Gas Exports Near Record 2024 Levels, Forecasts Show Continued Strength,” Pipeline & Gas Journal, accessed January 13, 2025, https://pgjonline.com/news/2025/january/norway-gas-exports-near-record-2024-levels-forecasts-show-continued-strength/.

[34] “Equinor’s Troll Field Sets New Production Record in 2024, Strengthening Europe’s Energy Security,” EuropaWire, accessed January 13, 2025, https://news.europawire.eu/equinors-troll-field-sets-new-production-record-in-2024-strengthening-europes-energy-security/eu-press-release/2025/01/06/14/54/41/146104/.

[35] European Commission, “Statement by President von der Leyen on Strengthening Europe’s Energy Independence,” European Commission Press Corner, accessed January 13, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_22_3975.

[36] “Will the Rapprochement Unlock the Full Potential of the Eastern Mediterranean’s Natural Gas Wealth?” ISPI Online, accessed January 13, 2025, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/will-the-rapprochement-unlock-the-full-potential-of-the-eastern-mediterraneans-natural-gas-wealth-194778.

[37] ECCO Climate, “Do we really need the EastMed pipeline?” May 16, 2022, https://eccoclimate.org/do-we-really-need-the-eastmed-pipeline/.

[38] East Mediterranean Gas Forum, “Overview,” accessed January 13, 2025, https://emgf.org/pages/about/overview.aspx.

[39] European Commission, “EU-Egypt-Israel Memorandum of Understanding,” accessed January 13, 2025, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/publications/eu-egypt-israel-memorandum-understanding_en.

[40] Eunice Group, “TILOS Project,” Eunice Group, accessed January 12, 2025, https://eunice-group.com/projects/tilos-project/.

[41] European Commission, “Alpgrids: Local Grids for Reliable Renewable Energy in the Alps,” European Regional Policy Projects, accessed January 13, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/Austria/alpgrids-local-grids-for-reliable-renewable-energy-in-the-alps.

[42] European Commission, “Press Release: Commission Proposes New Measures to Strengthen Energy Security in the EU,” IP/23/5787, accessed January 13, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_23_5787/IP_23_5787_EN.pdf.

[43] Ibidem.

[44] European Parliament, “Energy Policy: General Principles,” Fact Sheets on the European Union, accessed January 13, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/68/energy-policy-general-principles.

[45] European Commission, “Support Schemes for Renewable Energy,” Energy – European Commission, accessed January 13, 2025, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/financing/support-schemes-renewable-energy_en.

[46] European Commission, “Energy Storage,” Energy – European Commission, accessed January 14, 2025, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/research-and-technology/energy-storage_en.

[47] European Commission, “Recommendations on Energy Storage,” Energy – European Commission, accessed January 14, 2025, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/research-and-technology/energy-storage/recommendations-energy-storage_en.

[48] “Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners Poised to Build $800m BESS Projects in Scotland,” IPE Real Assets, accessed January 14, 2025, https://realassets.ipe.com/news/copenhagen-infrastructure-partners-poised-to-build-800m-bess-projects-in-scotland/10128079.article.

[49] Ibidem.

[50] European Economic and Social Committee, EU Digitalisation of the Energy System, March 2024, accessed January 14, 2025, https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-03/eu_digitalisation_of_the_energy_system.pdf.

[51] European Commission, “Press Release: European Commission Adopts New Measures to Accelerate the Energy Transition,” European Commission Press Corner, accessed January 14, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6228.

[52] “Europe’s Smart Energy Expert Group Holds First Meeting,” Smart Energy International, accessed January 14, 2025, https://www.smart-energy.com/policy-regulation/europes-smart-energy-expert-group-holds-first-meeting/.