Abstract

This paper examines Sino-Omani relations within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), highlighting their strategic significance for China’s expanding presence in the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Peninsula. Through a qualitative and analytical approach, drawing on existing literature and official data, the study explores China’s motivations for investing in Oman, Oman’s rationale for embracing the BRI, and the broader implications of this engagement. The findings suggest that Oman’s geographic location, neutral diplomatic stance, and regional connectivity make it a key strategic partner for China. Moreover, Oman’s participation in the BRI aligns with its efforts to leverage its geopolitical position while maintaining a balanced foreign policy. China’s growing presence in the Gulf may enhance Chinese firms’ competitiveness and contribute to rising tensions in the Strait of Hormuz.

Introduction

In the last few decades, the global scenario has been transitioning from a neat bipolarity to a dynamic and increasingly multipolar framework. Mostly due to the overwhelming trend of globalization, defined by influential scholar Robert Gilpin as the deepening and widening integration of the world economy by trade, financial flows, investment, and technology, have been experiencing significant economic and technological growth.[1] Countries like Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Nigeria and, most importantly, China, are the great protagonists of this trend. As Beijing continues to expand its overseas influence, its challenge to US supremacy is one of the most important motors of change towards a new era of International Relations. Among the countries that have entered China’s sphere of influence, there is one that has done so by exploiting its traditional neutral foreign policy line, cleverly placing itself at the centre of a conflict of interests of the “Goliaths” of the globe. The Sultanate of Oman, a country often overlooked in international relations literature, is leveraging its strengths intelligently, designing a functioning foreign policy tailored to its geographic location, resources, and needs.

China’s interest in Oman within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is particularly significant. China has engaged, in the last few decades, in investments in the whole Middle Eastern area, reaching 136 billion USD from 2005 to 2016, as well as in currency swap agreements between the People’s Bank of China and local central banks.[2] Interestingly, China has allocated a proportionally higher number of resources to Oman compared to much richer actors in the region. According to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, Oman’s trade with China has grown at an annualized rate of 9.84% over the past five years, rising from $18.9 billion in 2018 to $30.2 billion in 2023 it’s higher, in absolute terms, than that of much richer Egypt, and even more significant when considering the size of Oman’s economy, whose GDP currently stands at around $109 billion.[3]

The Sultanate has the potential to serve as a pivot in China’s trade routes, providing a gateway to the broader Arab region and, ultimately, to Europe. This paper seeks to explore the geopolitical and strategic rationales behind China’s engagement with Oman; it will then cover the rationales between Oman’s decision to join the BRI; finally, it will explore the major implications of this partnership, shedding light on an underappreciated yet powerful protagonist of the Gulf region.

China’s interest in Oman

The main rationales of China’s interest in Oman are its geographic position, its role in energy routes management and its stable diplomatic stance in the international and regional scenario.

Geography

The Sultanate lies in a strategically strong position on the southeastern coasts of the Arabian Peninsula, sharing borders with Saudi Arabia, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, and facing Iran on the other side of the Gulf. As the geopolitical importance of the Indian Ocean rises, now accounting for half of the world’s container traffic and 70% of its petroleum shipment, Oman is a perfect base for military use and logistical support, while at the same time allowing for the design of new paths for the Maritime Silk Road.[4] China is interested in securing a port on the Omani coastline to facilitate the trade route from Gwadar, as the Pakistani port is connected to one of the strongest arteries of the New Silk Road: connecting Gwadar to the Middle East means connecting Xi’an, in the very core of the “new empire”, to the Arabic world.

Energy

The Sultanate is separated from Iran by the Gulf of Oman, with its most narrow point, the Strait of Hormuz, connecting it to the Persian Gulf. The Strait is among the world’s most important oil chokepoints: according to Strauss Center data, oil tankers carry approximately 17 million barrels of oil per day through the Strait, accounting for 20 to 30 percent of the world’s total consumption.[5] In 2015, China became the world’s largest importer of oil, and despite Beijing’s attempt to look for alternative energy sources, half of its oil imports still come from Middle Eastern countries.[6] Since the early 1980s, Oman became the first Arab nation and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member to export oil directly to China, and despite its relatively small reserves compared to Middle Eastern standards, oil sales remain the main axis of the connection between the two countries.[7]

Diplomatic stance

Since the arrival to power of Sultan Qaboos in 1970, the most prominent feature of the Omani foreign policy has been “positive neutrality”. During the 2007 national celebrations of the Sultanate, Qaboos defined Oman’s foreign policy line by saying: “The features of foreign and internal policy are based on neutrality and comprehensive, sustainable development, and at the same time on friendship, peace, positive dialogue, coexistence, and avoiding conflicts”.[8]

This is exemplified by Oman’s stance during the Syrian crisis since 2011, where it rejected armed operations aimed at overthrowing President Bashar al-Assad, and the Sultanate’s decision not to interrupt bilateral diplomatic ties with Syria, unlike the other members of the GCC.[9] In the Yemeni crisis, Oman refused to intervene militarily with its armed forces, assuming the role of mediator between Saudis and Houthis rebels. Similarly, during the 2011 uprisings in Libya, Oman again showed its commitment to the neutral paradigm, deciding not to intervene; instead, the Sultanate hosted talks between the warring factions in an effort to broker peace.[10] In the past few decades, Oman has earned the title of “mediator of the Middle East”, working as a bridge between the Gulf region and the rest of the world.

Indeed, the Sultanate is very well inserted into Gulf politics. It is a member of the GCC, the most important international organization of the Middle Eastern countries, especially relevant in the realm of oil production. With regards to oil, Oman is not a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and doesn’t strictly depend on its decisions but adheres to OPEC-plus quotas with voluntary cuts. Such coordination of oil production policies with the group is the first witness of its involvement in Gulf Politics.

Secondly, the relations between Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as well as between Oman and Saudi Arabia, are flourishing in the context of infrastructural development. In November 2022, Oman Rail and Etihad Rail from the UAE launched a partnership to build a $3 billion railway network, with the final aim being connecting all six GCC monarchies by rail, with the objective of enhancing the potential of the Sohar port and free zone in northern Oman by linking it with the UAE’s national railway network.[11] In May 2023, Oman and the Emirati Etihad Rail Company signed an agreement to use the railway to transport iron and its derivatives between the Sultanate and the UAE.[12]

At the Saudi Omani Investment Forum held in Riyadh in early 2023, Saudi and Omani instituted the integrated Special Economic Zone of Al-Dhahirah in Oman’s inland governorate, near the Saudi border. On the same occasion, an agreement was signed to foster investments and bilateral cooperation between Special Economic Zones and free zones, with specific emphasis on Oman’s strategically positioned Duqm (Special Economic Zone) and Salalah (free zone) along the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea, respectively. It is straightforward to not how, by developing stable diplomatic relations with Oman, China would increase its chances of strengthening its influence over the Arab region.

Oman’s interests in the BRI

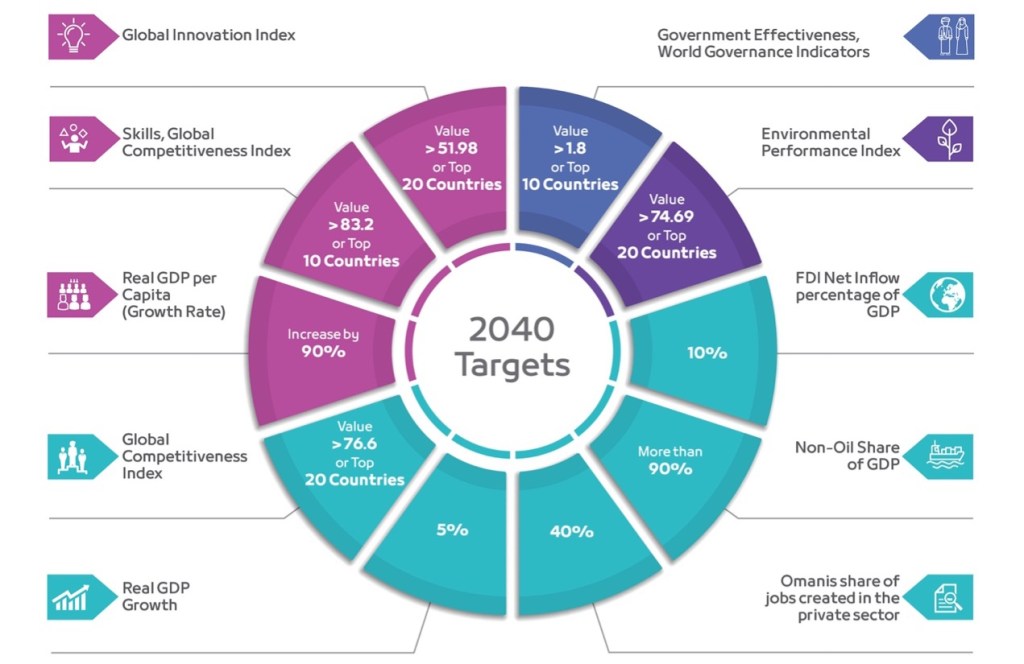

Oman’s interests in adhering to the BRI are rooted in its economic challenges. Oman’s economy, heavily reliant on oil production, has been facing a crisis due to fluctuating oil prices since 2015, when the oil industry accounted for 33.9% of the national GDP, and due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In December 2020, Sultan Qaboos Bin Said launched the Oman Vision 2040 program, a “national reference for economic and social planning”, reflecting Oman’s desire to leave behind the model based on sole oil production and export.[13]he main goal of the project is to gradually replace the energetic sector with alternatives that can form a stable economic base and an internationally attractive private sector. Among the most significant examples are tourism, logistics, manufacturing, and agriculture.

A central passage of the implementation framework of Vision 2040 is that of the role played by Foreign Direct Investment. By opening the borders to Chinese capital flows in the last decade, Oman has been able to build the infrastructural foundations of a new diversified private market. The cooperation results in a win-win game: while providing regional influence and valuable connections for China, Oman gains substantial growth opportunities. A particular focus is on the development of coastal infrastructures. Strategic coastal planning, which includes the development of ports, logistics and commercial infrastructure, is crucial to allow the free circulation of investments and technologies. In this direction, Vision 2040 Project entails the strengthening of important ports like those of Sohar and Duqm.[14]

The port of Sohar is situated on the northern coast of Oman, approximately 200 km northwest of Muscat, its location being its first real strength. It is located just before the previously mentioned Strait of Hormuz, providing great connectivity to hubs like Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Riyadh. The port is managed by the Sohar Industrial Port Company (SIPC), with the primary objective of creating an attractive investment package for foreign maritime and industrial activities. To date, the port has received investments from prominent Chinese players, above all China National Chemical Engineering Group Corporation (CNCEC), supervised by State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council of China.[15]

Moving Southwest, the Industrial Park in the Duqm Special Economic Zone (DSEZ) is arguably the most representative example of cooperation between China and Oman. In 2016, Oman welcomed a Chinese consortium, Oman Wanfang, to develop a new industrial city, transforming Duqm, a former fishing village, into the most ambitious BRI project in the Middle East. Located on the Southeastern Arabian coastline, about 550 km south of Muscat, the port is the most important connecting point of the Maritime Silk Road with trade routes between the Arabian Peninsula, Europe, East Africa and East Asia. Oman Wanfang Company is planning to implement 35 projects in the area, which will be organized into three zones: one focused on heavy industries such as methanol, petrochemicals, natural gas, steel smelting, aluminum, vehicle tires, and magnesium; another zone dedicated to light and medium industries including solar power units, batteries, SUVs, oil and gas tools, and pipelines; a third zone will be dedicated to the tourism sector hosting a hospital, a school and a $200 million five-star tourism zone entailing hotels and restaurants.[16]

Major implications

An increased presence of the Dragon in Oman and, more broadly, in the Arabian Peninsula will inevitably impact trade in the Mediterranean. The development of ports along Oman’s southeastern coast will enhance trade routes connected to Pakistan’s Gwadar port, a key junction where the land and maritime components of the New Silk Road converge. This enhanced connection is expected to increase trade volumes in the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal.

Over the past decade, China has solidified the role of the Mediterranean as the terminal for routes departing from Far East Asia with heavy investments in Mediterranean port infrastructure. China’s Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), China’s largest state-owned shipping company, heavily funded coastal developments in Egypt, Turkey, and Greece, making the port of Piraeus a real gateway to Europe.[17] As China strengthens its connectivity to the Mediterranean through ports like Duqm and Sohar, potentially using them as refueling points, the volume of shipping is expected to rise while relative transportation costs decline. In the next decade, European companies should be ready to face increasingly competitive Chinese counterparts that will be able to export more goods and sell them at lower prices in the European markets.

Beyond trade, new variables must be added to Europe’s energy security calculus, as China’s efforts in securing long-term energy contracts with Gulf producers may have a tightening effect on European buyers’ oil supply opportunities. The local strengthening of Chinese state-backed energy companies represents a dangerous and potentially unsustainable competition for European firms such as British Petroleum (BP) and Shell, which have traditionally (and recently) invested in the Sultanate’s Liquified Natural Gas reserves.

The growing Chinese presence in the Strait of Hormuz will impact both energy prices and the delicate equilibrium of the region, as this critical energy gateway hosts multiple military forces deployed by powers from all over the world. Nine European countries currently maintain a military presence in the region under the European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASoH), a French-led project that brings together the navies of European countries in protecting flows from piracy.[18] The United States as well has long maintained a strong military presence in the Strait to protect the investments of American oil companies. This presence was reinforced in 2023, despite US efforts to reduce dependence on Gulf oil, after episodes in which the Iranian navy blocked American oil tankers under the pretext of intercepting smuggled Iranian oil.[19]

Indeed, since the American withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018, Tehran has resolutely been replacing Washington as an exporting partner with various non-Western powers, primarily China. In this sense, Iran has offered discounted oil prices and signed a 25-year strategic cooperation agreement with Beijing.[20] This partnership has reinforced China’s position in the Gulf, with the People Liberation Army Navy conducting joint drills alongside Russian and Iranian forces in 2023 to “deepen practical cooperation”.[21]

Additionally, China’s investment in coastal infrastructure in Oman now provides an operative base in the Strait for Chinese naval ships, which already patrol local waters to counter piracy against oil tankers. Given that 40% of China’s oil imports transit through Hormuz, Beijing is interested in securing stability in the region, thus some scholars argue that an escalation in Hormuz is neither certain nor likely to happen.[22] As the largest importer of oil through the Strait, China is the most vulnerable country to any disruption in the free flow of oil tankers. However, Western powers remain concerned about China’s exponential gain of influence in the region, which, in the near future, may shift progressively from commercial to military-driven.

Conclusions

The increasing Chinese investments under the Belt and Road Initiative highlight Oman as a protagonist in the Gulf region. Its strategic position, its role in energy security and its stable diplomatic stance in the international scenario makes it a perfect investment terminal for Beijing, which has been exploiting this opportunity, particularly in the last decade. By acting as a mediator both within the region and on the global stage, Oman is able to guarantee stable returns on investment for China, strengthening its influence over the Arabian Peninsula.

On the other hand, Oman warmly welcomed Chinese investments, essential to address the challenges of economic diversification and to meet the need of creating new markets and jobs for its growing workforce. The implications of this relationship extend far beyond the Gulf, with the potential to reshape Mediterranean trade flows and intensify competition in European markets. European companies and policymakers should expect and be ready to anticipate a further increase in Chinese firms’ competitiveness. Furthermore, as China deepens its influence in the Strait of Hormuz, geopolitical tensions may arise, impacting the balance of power in a region traditionally dominated by Western and Gulf powers. While a military escalation seems unlikely today, scholars foresee a future where China’s presence in the Gulf becomes more entrenched, at the expenses of an increasingly absent West.

Cover image: Ceremony of ground-breaking for China-Oman Industrial Park – Duqm. Source and Credit: Oman Economic Review

[1] Sylvia Ostry. 2001. “The Challenge of Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century. By Robert Gilpin, with the Assistance of Jean Millis Gilpin. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000, 257” American Political Science Review 95 (1): 257–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055401822012.

The concept of “global periphery” refers to countries or regions that are economically, politically, and strategically marginalized in the global system. These areas often experience structural disadvantages due to historical experiences of colonization, economic dependency, and limited access to global decision-making processes. The term is rooted in World-Systems Theory, developed by Immanuel Wallerstein, which divides the international scenario into core, semi-periphery, and periphery.

[2] Maha S. Kamel, 2018. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Implications for the Middle East.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 31 (1): 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2018.1480592.

[3] “Oman (OMN) and China (CHN) Trade | the Observatory of Economic Complexity,” The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/omn/partner/chn?redirect=true.

[4] Mordechai Chaziza, 2018. “The Significant Role of Oman in China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative.” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 6 (1): 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347798918812285.

[5] “Strait of Hormuz – about the Strait,” The Strauss Center, n.d., https://www.strausscenter.org/strait-of-hormuz-about-the-strait/.

[6] See note 4

[7] Ibidem

[8] Sigurd Neubauer, 2016. “Oman: The Gulf’s Go-Between.” https://agsiw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Neubauer_OmanMediator.pdf.

[9] Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

[10] Eleonora Ardemagni, 2023. “Oman: Tutte Le Partnership Di Un Paese Neutrale | ISPI.” ISPI. July 15, 2023. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/oman-tutte-le-partnership-di-un-paese-neutrale-135525.

[11] Ibidem

[12] Ibidem

[13] Zhibin Han and Chen Xiaoqian . 2018. “Historical Exchanges and Future Cooperation between China and Oman under the ‘Belt & Road’ Initiative.” International Relations and Diplomacy 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2134/2018.01.001.

[14] Oman Vision 2040 Booklet (Muscat: Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit), 12.

Mary Kate Smith, “Duqm Is Oman’s Pathway to the Future,” Gulf International Forum, September 4, 2024, https://gulfif.org/duqm-is-omans-pathway-to-the-future/.

[15] Arab-China Institute for Economics and Policy. 2024. Arab-China Institute for Economics and Policy. April 2024. https://www.aciep.net/en/2024/04/01/214/.

[16] Hamdan Al Fazari and and Jimmy Teng. 2019. “Adoption of One Belt and One Road Initiative by Oman: Lessons from the East.” J. For Global Business Advancement 12 (1): 145. https://doi.org/10.1504/jgba.2019.10021555.

[17] Enrico Fardella , and Giorgio Prodi. 2017. “The Belt and Road Initiative Impact on Europe: An Italian Perspective.” China & World Economy 25 (5): 125–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12217.

[18] https://www.emasoh-agenor.org/

[19] Sam Fossum, 2023. “US Bolstering Defense Posture in the Persian Gulf after Iran Seized Two Merchant Ships in Recent Weeks.” CNN. May 12, 2023. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/12/politics/us-iran-persian-gulf/index.html.

[20] Ghazal Vaisi, 2022. “The 25-Year Iran-China Agreement, Endangering 2,500 Years of Heritage.” Middle East Institute. March 1, 2022. https://www.mei.edu/publications/25-year-iran-china-agreement-endangering-2500-years-heritage.

[21] Liiu Huanzun and Guo Yuandan. 2024. “China, Iran, Russia Wrap up Sea Phase of Joint Naval Exercise – Global Times.” Globaltimes.cn. 2024. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202403/1308837.shtml.

[22] Abdullah, Baabood, 2023. “Why China Is Emerging as a Main Promoter of Stability in the Strait of Hormuz.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2023. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/05/why-china-is-emerging-as-a-main-promoter-of-stability-in-the-strait-of-hormuz?lang=en¢er=middle-east.