Abstract

Critical Underwater Infrastructure (CUI) security has become a strategic priority for Europe, particularly as hybrid threats and sabotage operations intensify. The Baltic Sea Region (BSR) has developed a well-functioning model to protect CUIs through regional cooperation, intelligence sharing, rapid response capabilities, and a significant NATO presence in the area. However, replicating this model in the Mediterranean presents challenges due to its political fragmentation, contested maritime zones, and diverse threat spectrum and how it is assessed. This paper examines the Baltic experience of securing CUIs and explores how Mediterranean countries can adapt the BSR model’s core principles through enhanced NATO-EU coordination, fostered strategic autonomy, and renewed and reconceptualised regional partnerships. In an era where CUIs are conceived as a strategic advantage and vulnerability because of their dual nature of economic lifelines and geopolitical pressure points, the Mediterranean must adopt a tailored security approach to counter rising hybrid threats based on the lessons matured by the BSR.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022, five incidents involving underwater infrastructure have occurred in the Baltic Sea. As this region became even more critical due to its role as a significant European hub for energy pipelines and undersea communication cables connecting Northern Europe, underwater infrastructures have increasingly become targets for potential sabotage and hybrid operations, raising questions about their protection and resilience.

These events widened the attention to Russian hybrid tactics in the region. As an area of strategic importance for European countries, the Baltic region represents the perfect hotspot for Russia to have leverage outside the region, especially with the European Union (EU) and NATO, and amplify its aura of invincibility through strategies of plausible and implausible deniability.[1]

However, especially after the Russian annexation of Crimea, Baltic and Nordic countries have reinforced their posture to resist such disruptions, adopting a multifaceted and multi-layered approach. This approach was strengthened by the recent accession of Finland and Sweden to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which has expanded regional security cooperation and deterrence capabilities.[2] The Baltic model offers a case study of how states facing persistent hybrid threats can fortify critical underwater infrastructures through coordinated defence strategies despite initial differences and approaches.

Despite geopolitical and structural differences, the Baltic and Mediterranean regions share a key vulnerability: their dependence on the underwater domain for energy security and communication infrastructure. Indeed, as a critical, highly congested transit zone hosting vital global energy and communication infrastructures, the Mediterranean Sea represents a crucial area of strategic vulnerability for countries with their assets on the seabed. This area presents a more complex security environment than its Baltic counterpart, characterised by political fragmentation, contested maritime zones, and overlapping regional interests, which also risk becoming the next battlefield of international competition.[3]

This paper examines the matured Baltic region’s experiences in countering Russian underwater threats to Critical Underwater Infrastructure (CUI), exploring how Mediterranean countries, highly reliant on underwater infrastructures, can adapt the Baltic model through a tailored approach rather than a direct replication due to the region’s peculiarities in an era of increased geopolitical competition.

The Baltic arena: strategic dependence and the European path

Since regaining independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union, aware of the political and security risks, the Baltic countries – namely Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia – have adopted a strategy to disentangle from Russian energy and communication infrastructure.[4] Until 2014, the year of Russia’s unilateral annexation of Crimea, the Baltic region was considered an “isolated energy island” in Europe for two main reasons: its heavy dependency on the Russian energy supply and the synchronisation of its grids with Russia[5].

Before 2014, the structural dependence on Russian energy resources was one of the most critical issues in affirming political alignment with the West and NATO, allowing the Kremlin to influence Baltic countries through coercive policies.[6] In 2013, 85% of Lithuania’s fuel imports came from the Russian Federation. Although it seemed to be to lower degrees, even Latvia was still heavily dependent on Kremlin resources.[7] Moreover, after their independence, the Baltic states remained interconnected to Russia through the Belarus-Russia-Estonia-Latvia-Lithuania (BRELL) power grid, the Baltic part of the IPS/UPS power grid ring. This continued until the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region and the Baltic Energy Market Interconnection Plan (BEMIP) was implemented.[8]

However, the Baltic states, led mainly by Lithuania, have made enormous strides over the past decade, achieving complete independence from Russian energy. Baltic states rapidly shifted their energy strategies, investing in critical infrastructure such as the NordBalt cable (Sweden-Lithuania), EstLink cables (Finland-Estonia), and the LitPol Link (Lithuania-Poland), as well as in several communication undersea cables, making the Baltic Sea one of the most congested seabed areas in the World. In addition, in the aftermath of the Ukrainian war, they banned gas imports from Russia, agreeing to synchronise their electricity grid with the Continental European Network through LitPol Link on 8 February 2025, which will be added to the Harmony Link, planned for 2030.[9]

Source: European Commission

Russian hybrid tactics: operating in the grey zone

Baltic states’ disentanglement strategy, of which infrastructural reforms are a pillar, has left the region particularly vulnerable to hybrid threats, mainly by Russia. These threats encompass supply manipulation – before becoming independent from the energy standpoint – and disruption, price hikes, disinformation campaigns, political pressure, and cyberattacks. Such tactics are designed “to achieve goals gradually without triggering decisive responses […] mainly target[ing] the will of the people and the decision-making ability of the government.”[10] In other words, these tactics aim to destabilise the region and send a political message to NATO and the EU, challenging their capabilities to safeguard their critical infrastructures.

Over the last decade, several incidents have targeted undersea infrastructure in the Baltic, particularly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The most recent occurred on January 26, 2025, when a Latvian fibre optic cable (LVRTC) was disrupted in Swedish waters. [11] Just a month earlier, on December 25, 2024, the Russian vessel Eagle S severed the Estlink 2 connection between the Nordic and Baltic countries by dragging its anchor. [12] These incidents, accompanied by the one against the BalticConnector, NordStream 2, the BCS East-West Interlink and C-Lion1 fibre-optic cables, underscore an escalation of hybrid threats to critical undersea infrastructure. [13]

While Russia has denied its responsibility, there is a broad consensus that it is accountable for most accidents in the Baltics. As such, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Kaja Kallas, said that “sabotage attempts in the Baltic Sea are not isolated incidents” but rather “part of a deliberate and coordinated effort to target our digital and energy infrastructure.”[14]

These inherently ambiguous operations capitalise on the complexity of attributing liability and the uncertainties generated by such difficulty. This is particularly evident in the underwater domain, where the combination of plausible deniability – as well as implausible deniability – relatively low technical barriers and the strategic importance of infrastructure create an environment ripe for hybrid threats.

This ambiguity enables malicious actors to exploit the information vacuum, spreading disinformation to feed public opinion, with disinformation eroding public trust in institutional responses.[15] Indeed, as Gehringer points out, a complete interruption of all data traffic is unrealistic because backup capabilities, energy deposits and supply chain recoveries are put in place to avoid complete and prolonged disruption of services. [16] However, delays and temporary disruptions may occur, endangering public trust in institutions, undermining the feeling of security within the society and giving adversaries an aura of invincibility, sending a message that any Baltic or Nordic country can be hit anywhere and at any time.[17]

Baltic Security: a Cooperative Approach in Securing Strategic Assets

Common Region, Common Threats

In coordination with Nordic countries, Baltic states have developed several frameworks for cooperative security in the Baltic Sea to counter Russian efforts. These security frameworks encompass a whole-of-government approach or “Total Defence”[18], typical of these countries.[19] These approaches not only tackle underwater security through regional military cooperation but also provide a framework to protect state foundations from disinformation, propaganda, corruption, cyberattacks, and the entire arsenal of hybrid tactics with the involvement of civil society and measures throughout the DEMIFIL spectrum.[20] Indeed, in the words of Commander MARCOM, Royal Navy Vice Admiral Mike Utley,

“securing CUI goes beyond posturing to deter future aggression; it includes robust coordination, to actively monitor and counter malign or hybrid threats, denying any aggressor the cover of plausible deniability.”[21]

This Nordic-Baltic cooperation is allowed by shared interests, shared region’s threat assessments, and extensive participation in international and regional institutions and organisations. This happened in contrast with their historical approach, previously driven by differing strategic and geopolitical interests.[22] Applying what Opitz stated about narrow defence and broader security perspectives to those countries, it may be described that while Baltic countries perceived Russia primarily as the traditional military threat, Nordic countries comprehended Russia more broadly as a latent uncertainty factor with hybrid threat potential.[23]

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 played a pivotal role in the realignment of powers in the region, forcing a reassessment of security priorities, particularly about Russia’s conventional and unconventional threats. The realignment led to Sweden and Finland joining NATO, abandoning their historical policy of neutrality[24]; Denmark’s removal of the opt-out from the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP); and a reinforced mistrust towards Russia by Poland and the Baltic states, shared by Nordic countries and Germany.[25] This realignment has enhanced NATO’s presence in the region, strengthening deterrence and rapid response mechanisms, including improved cybersecurity resilience and increased private sector involvement, and the integration of cutting-edge technology, particularly in securing CUI.[26]

The Baltic Region and Nordic partners have strengthened relationships by adjusting their priorities to include hard security concerns, total defence integration, and increased interoperability in peace, war, and crisis times.[27] Regional forums, such as the Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO) and the several Nordic-Baltic formats, especially those regarding the involvement of Great Britain and the United States, have facilitated dialogue on key issues.[28]

However, difficulties remain due to the nature of undersea cables, which cross territorial waters, exclusive economic zones and high seas, and coordination challenges between private operators, navies, police and coast guards, where responsibility distribution varies from country to country.[29]

NATO & EU’s Role in Underwater Security

NATO and the EU, considered the most capable actors in addressing unconventional threats, remarkably improved their presence in the Baltic Sea Region (BSR) by prioritising maritime security. Yet, in 2022, the NATO Strategic Concept underlined that “maritime security is key to our[NATO countries’] peace and prosperity” and that NATO needs to strengthen its posture to “deter and defend against all threats in the maritime domain.”[30]

Since then, at the strategic level, NATO launched a CUI Coordination Cell in Brussels to map vulnerabilities and synchronise efforts between governments and the private sector, coupled with the EU-NATO joint Task Force on the Resilience of Critical Infrastructure. In addition, at the Union level, the revised EU Maritime Security Strategy in 2023 and its Action Plan set the strategic objectives and operational primary goals to reinforce Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), information-sharing and the overall spectrum of maritime security.[31] Furthermore, the EU Commission’s “Recommendation on secure and resilient submarine cable infrastructures” is also very significant, as it includes recommendations for states at both national and Union levels. At a domestic level, it recommends more frequent risk assessments and stress tests on subsea cable systems’ cyber and physical security, while at the Union level, a common framework to assess risk, vulnerabilities and dependencies and the improvement of the shared information environment.[32]

At the operational and military level, NATO significantly enhanced its presence. The Alliance started to include CUI protection scenarios in its exercises, such as the June 2024 BALTOPS, and invested increased focus on anti-submarine warfare, as shown by the Freezing Winds exercise.[33] In July 2023, NATO’s Maritime Center for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure (MCSCUI) was established in the UK as the operational branch “to coordinate efforts between NATO Allies, partners, and the private sector”.[34] Moreover, from its traditional competencies, the Joint Expeditionary Force has begun to contribute to the protection of CUI in the BSR.[35] Furthermore, in January 2024, following the most recent accidents, NATO launched the Baltic Sentry operation, involving various assets and new technologies to secure the seabed, ranging from multi-layered surveillance to military presence to deter any adversarial action.[36]

Multi-Layered Approach to Underwater Domain Awareness

One of the most relevant steps made by Baltic and Nordic countries is the employment of a multi-layered approach to the underwater domain and improved information sharing between the parties. Indeed, until the 2017 BALTOPS, there was no complete picture of the Baltic Sea’s air, surface, and subsurface domains. Since then, they have filled that vacuum dubbed “sea blindness”, dedicating resources to improve national, regional and European maritime C4ISR* capabilities and information sharing.[37] Through initiatives like the Sea Surveillance Cooperation Baltic Sea (SUCBAS) and the Baltic Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA-BSR) framework, Nordic and Baltic countries have established real-time data exchange networksthat allow for continuous monitoring of suspicious vessel movements and underwater anomalies.[38]

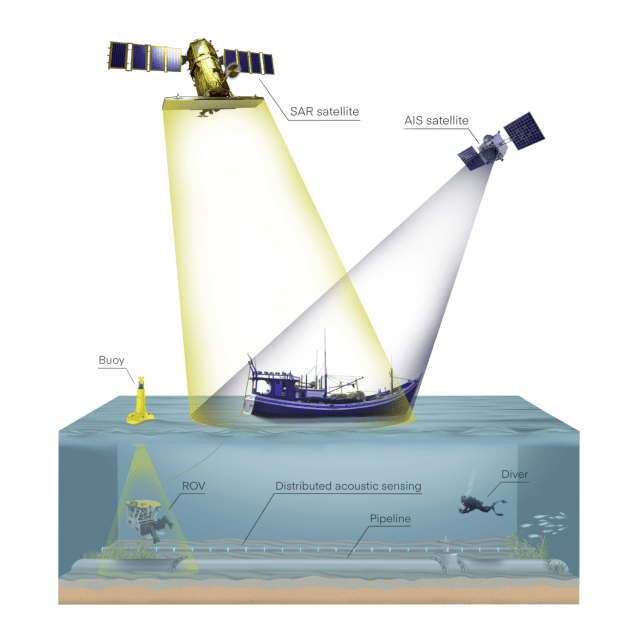

These initiatives are coupled with the NATO Critical Undersea Network (NCUN), aimed to improve information sharing and coordination for the security of CUI and new technological applications in undersea awareness, such as the employment of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and a Seabed-to-Space Situational Awareness (S3A) strategy.[39] Moreover, a strategic pivot towards private involvement has facilitated this technological development and deployment, including risk assessment and unclassified intelligence sharing, enhanced cybersecurity measures and norms development, and cooperation through specialised centres such as the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence and the NATO Energy Security Centre of Excellence.[40]

Despite persistent challenges, such as jurisdictional complexities, the coordination of national authorities, and the hybrid nature of threats, the Baltic may be considered a successful model for mitigating maritime threats, especially those regarding CUI. This approach highlights a strategic vision based on a multi-layered and cooperative security framework that provides regional interoperability and information-sharing, total defence principles, and a sustained commitment to infrastructure security through the involvement of the private sector and improved integration of military and civilian capabilities.

Source: Soldi, G., Gaglione, D., Raponi, S., Forti, N., d’Afflisio, E., Kowalski, P., Millefiori, L. M., Zissis, D., Braca, P., Willett, P., Maguer, A., Carniel, S., Sembenini, G., Warner, C. 2023. Monitoring of Underwater Critical Infrastructures: The Nord Stream and Other Recent Case Studies. February 2. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.01817.

The Mediterranean Region: complexities, challenges and advantages

Challenges: Mediterranean disadvantage

Mediterranean nations share some similarities with the Baltic region, as they face increasing maritime competition and risks of hybrid threats. Due to the rise of the threat level, developing a maritime strategy to protect critical undersea infrastructure and ensure long-term resilience in an evolving threat environment becomes vital at the national and, most importantly, regional levels. However, while the Baltic region is often called the “NATO lake,” benefiting from a high degree of political cohesion, military interoperability, and a shared threat perception regarding Russia, the Mediterranean presents a far more complex and fragmented security landscape.[41]

The Mediterranean’s security environment is characterised by several factors, such as the high congestion level, the diversity of threats in the region, how they are assessed by regional actors, and its coastal states’ often conflicting national interests. These factors create significant obstacles to implementing a Baltic-style security architecture, such as eroding trust between parties and increasing the threat level.

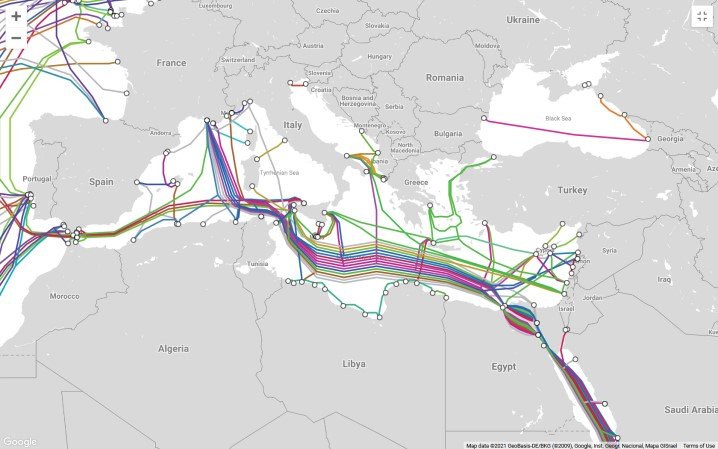

The Mediterranean region is one of the world’s most strategically significant but geopolitically volatile maritime areas. Despite occupying only 1% of the world’s water surface, it accounts for over 20% of global maritime traffic and 16% of global internet traffic, serving as a crucial link between Africa, Europe, and Asia. Additionally, the Mediterranean facilitates 30-35% of strategic gas and oil routes, supplying up to 65% of Europe’s energy needs, and hosts key telecommunications infrastructure.[42] Unlike the Baltic, where NATO and the EU provide a common strategic framework, the Mediterranean has multiple overlapping regional organisations, differing security and strategic priorities, and competing threat perceptions among its littoral states.

This complexity is further amplified by the concept of the Enlarged Mediterranean, which extends beyond the sea itself to encompass the Red Sea, the Black and Caspian Seas, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and parts of the Atlantic close to North Africa and Europe. [43] This broader regional security complex underscores the Mediterranean’s role as a theatre of global competition, also recognised as one of the world’s most volatile areas, far from being “a common area of peace, stability and shared prosperity” as declared in the 1995 “Barcelona Declaration”.[44] Regional stakeholders include France, Italy, Türkiye, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and extra-regional actors such as Russia and China. However, unlike in the BSR, the Mediterranean region is also characterised by a high presence of non-state actors, from pirates to terrorist groups, from militias to armed groups.

This political fragmentation, characterised by multiple interests and different regional approaches to Mediterranean issues, is the most significant obstacle to cooperation. Therefore, one of the complexities in replicating the Baltic model in the Mediterranean is the lack of a shared threat perception among regional actors. While in the BSR this shared perception of Russian threats drives cohesive defence policies, military cooperation, and intelligence-sharing frameworks, Southern flank states operate mostly alone. Even among EU and NATO members, perspectives diverge significantly.[45] For example, France and Italy frequently clash over key regional issues, including Libya and migration policies, undermining the potential for a coordinated EU response. However, this is a common challenge all over the area, as the threat assessment of Turkiye’s foreign policy by Eastern Mediterranean countries shows.[46]

At the same time, extra-regional actors like Russia and China add additional layers of competition and strategic ambiguity. This makes sharing real-time intelligence, coordinating anti-submarine warfare (ASW) operations, and protecting undersea infrastructure far more politically sensitive than in the Baltic because of the natural need for trust among parties and a strong political will.[47] Moreover, it could be exploited by malign actors that employ hybrid tactics. For example, they can exploit such a lack of cooperation to avoid control or boarding in contested EEZs.[48]

Furthermore, Mediterranean maritime security’s technical challenges are significantly more complex than those of the Baltic region due to the region’s size, depth, and congestion level. Unlike the Baltic, which is smaller and shallower – with an average depth of 55 meters – the Mediterranean is vast, deeply interconnected with global maritime flows – almost 220,000 merchant ships – and its average depth is 1,500 meters.[49] These characteristics make underwater surveillance and infrastructure monitoring considerably more difficult, making detecting deep-sea sabotage, covert submarine operations, and cable tapping harder.

Opportunities: Mediterranean advantage

While the Mediterranean region faces significant political and operational challenges in securing its CUIs, it also possesses distinct strategic advantages that can be leveraged to develop a resilient maritime security framework.

One of the Mediterranean’s primary assets is its advanced maritime economy, industrial capabilities and well-developed technological, infrastructural, and commercial expertise. This expertise is already involved in securing the maritime domain at the public and private levels. Moreover, public-private partnerships, state initiatives, and inter-organisational projects help coordinate state needs, assets, and private capabilities. Examples include the NATO Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) in La Spezia, Italy, and the SEACURE project, led by Thales, which involves 35 companies from 13 different EU countries.[50] A clear example of this collaboration between and among the private sector allies is represented by the test made during Exercise Bold Machina 2024. Here, Allied Special Operations Forces Command ran through detection systems to assess signature variations of systems provided by private companies.[51]

Another strategic leverage is the widespread presence of NATO’s initiatives in the region, which almost mirrors that in the Baltic Sea. Indeed, underwater domain strategy and initiatives, such as the NATO Ocean Vision, are shared among Allies, and projects might be applied across multiple regions and in a scalable way, adapting them to regional needs.[52] Task Force X, launched in the Baltic under the Baltic Sentry umbrella, will be multi-domain and applicable to NATO’s 360-degree approach. In coordination with other systems, such as the S3A NATO Mainsail, this Task Force comprises a fleet of autonomous systems to provide full underwater domain awareness (UDA).[53]

Moreover, although political fragmentation is the biggest issue in defining a common framework to protect CUI, it paradoxically represents an advantage. Indeed, while the Baltic region is mainly populated by NATO and EU countries and CUIs connecting these countries, the Mediterranean Sea is a multifaceted scenario characterised by interdependence between Asia, Africa, and Europe. This interdependence complicates sabotage operations, as an attack on critical assets in the Mediterranean could harm the economic and strategic interests of non-NATO actors, including Russia and China’s regional partners. This makes submarine warfare operations, cable tapping, or sabotage less likely, as they could jeopardise relations with their regional partners and allies

Source: TeleGeography

Conclusion & Recommendations

Recent events have shown that protecting critical underwater infrastructures emerged as a strategic priority for European countries for both the Northern border and the Southern flank amid rising hybrid threats, sabotage and geopolitical tension. However, while the Baltic region has developed a highly coordinated and NATO-integrated approach to maritime security that can respond rapidly and effectively to regional threats, the Mediterranean area presents a vastly more complex security environment. So, whereas a Baltic model provides valuable lessons about building resilience and deterring hybrid threats, it cannot be replicated in the Mediterranean region because it is neither feasible nor advisable due to its unique security dynamics.

The primary challenges preventing the complete replication of the Baltic model include the fragmented political landscape, the lack of a unified strategic vision among Mediterranean nations, and a broader spectrum of threats, including non-state actors and proxy conflicts. If the political geography of the Baltic allows for more homogeneous frameworks, such as NATO and the EU, facilitating greater inter-organizational cooperation, the Mediterranean requires more complex solutions. Despite structural differences, the Baltic experience underscores the importance of regional cooperation, intelligence sharing, and private-sector involvement in securing CUIs.

The region should address the political fragmentation and interoperability issues to adapt the Baltic Model to the Mediterranean security environment. These issues require a multi-level approach operating at the regional and EU-NATO levels. At the regional level, this should occur through a political recognition of the threat’s universality. Moreover, operationally, NATO-EU countries should promote tailored partnerships within the Southern neighbourhood, especially with those countries willing to cooperate and contribute to CUI protection, improving current programs and moving towards transactional relations where needed. Reclassifying information about UDA and MDA within the Alliance and towards partners should facilitate this regional approach, also allowing more efficient partnerships.

At the EU-NATO level, this should be realised through the harmonisation of NATO Mediterranean underwater security policies, avoiding fragmented national strategies that may not account for some aspects due to the inability or incapacity to address the issue alone. Thus, it would prevent fund inefficiency and unnecessary redundancy in systems and platforms and provide increased strategic autonomy. It would also prevent the proliferation of different approaches and perspectives and, consequently, a myriad of varying procurement programmes.

The first step towards a more secure Mediterranean underwater domain is political recognition of shared vulnerabilities in the region. Indeed, while Mediterranean actors may not share a common threat assessment, they share common vulnerabilities. This may enhance cooperation efforts in securing CUI by recognising the universal need to protect undersea cable and gas pipelines and the fact that greater coordination, information sharing, and interoperability are necessary to address the underwater threat. Moreover, it has to be recognised even towards those countries that are not allies but partners, moving beyond isolated initiatives and developing an integrated, coordinated – if not cooperative – approach, where the economic and strategic importance could serve as a strong incentive to overcome political divisions.

As such, the Alliance should improve cooperation with other Mediterranean countries within the framework of the Med Dialogue and the practical cooperation pillar. This may manifest through new Individually Tailored Partnership Programmes (ITPPs) that comprehend CUI protection, common exercise and training and established framework for Information sharing about MSA and UDA.[54] Signification attention should be dedicated to the Partnership Interoperability Initiative (PII) to enhance cooperation in CUI accident prevention, detection, and response with Southern Mediterranean countries such as Morocco and Tunisia.[55] These initiatives, coupled with clear common standards and best practices, may allow for overcoming some cooperation issues, giving NATO’s partners the means to counter hybrid threats to CUI. Moreover, within the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre (EADRCC) framework, NATO should extend its capacity-building work and civil protection exercises to CUI crisis response and enhance national resilience through improved disaster preparedness for major events.

This cooperation may be improved by reducing overclassification and with a consensus over priority partners. Firstly, overclassification impedes partners from being involved adequately, creating communication barriers that impact the effectiveness of reaching strategic goals, such as CUIs protections. Secondly, as suggested by Nicolò Fasola, NATO should rethink its partnerships strategically, where they should enhance and complement Allied strategic priorities. Translating his thoughts to the Mediterranean region, most Southern countries may be considered potential Tier 3 partners, that is, partnerships in which “relationships should be transactional, focusing on achieving issue-specific relative advantages over NATO’s peer competitors.”[56]

Moreover, while a common investment strategy for Defence and Security is feasible in the Baltics due to their participation in both NATO and the EU, this is far more complex in the Mediterranean region. However, NATO countries, especially those in the EU, should promote a common strategic framework concerning the underwater domain to facilitate coordinated cooperation and common and complementary procurement. While developing a national strategy is essential, primarily because states have the first responsibility to CUI protection, coordination and standardisation should be foundational for the NATO countries in the Mediterranean. Therefore, while adopting their national underwater strategies, major players such as France, Italy, and Spain should coordinate their procurement efforts to enhance interoperability and foster national and European industrial capabilities through Joint ventures. Significant improvements have been made on this issue, as shown by the six projects developed regarding the underwater domain in the context of Permanent Structured Cooperation and with the contribution of the European Defence Fund.[57]

Lastly, Mediterranean NATO-EU industrialised states should enhance their strategic autonomy in constructing, maintaining, and repairing critical submarine cable infrastructure by investing in localised production capabilities and fostering regional partnerships. A key aspect of this resilience is reshoring and friend-shoring practices, coupled with fostered domestic industrial capabilities, as shown by France’s reacquire of Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN) in 2024, previously sold to the Finnish Nokia. ASN is one of the four major companies in undersea cable production and the market leader in 2024, both in terms of new systems installed and total kilometres of cable produced from 2020 to 2024. Even Italy is attempting to buy the TIM subsea cable unit Sparkle, highlighting the increased focus on the underwater domain and strategic autonomy.[58]

This approach has also been embraced concerning ships dedicated to undersea cables, as three of the biggest companies managing cable fleets are located in Europe (two in France and one in the UK)[59]. However, critical vulnerabilities should be addressed, such as a possible shortage of available ships during a major crisis or war. Indeed, while Mediterranean countries could effectively respond, intervene, repair and substitute undersea cables during minor crises, this efficiency may be less during major crises or in a war scenario.

While domestic – and even at the European level – production may be expensive and anti-economic, the long-term strategic benefits, such as reducing reliance on non-allied actors, increasing supply chain security, and strengthening national resilience, outweigh the costs of not being prepared for significant disruptions and crises. Moreover, as previously highlighted, such immediate response capabilities have to be understood as a mean to be used over the whole spectrum of war. Improvements in rapid response mechanisms and capabilities might reduce the threat to the public trust in institutions and the sense of insecurity within the society after an attack short of war.

In conclusion, the Mediterranean region and its vulnerabilities have become a central issue for its littoral states and their allies due to the ever-increasing hybrid threat to critical underwater infrastructures. However, while the Baltic Sea Region is an efficient model to prevent, deter, counter and respond to hybrid threats, its direct replication is unfeasible in the Mediterranean region. Nevertheless, the core principles of the Baltic model – regional cooperation, intelligence sharing, industrial and strategic autonomy and rapid response capabilities – offer a valuable blueprint to adapt the model to the Mediterranean political and security environment. Strengthening strategic autonomy in undersea infrastructure, harmonising NATO-EU security policies, and fostering pragmatic partnerships with Mediterranean states will be essential steps toward mitigating vulnerabilities. In an era where maritime infrastructure is both an economic lifeline and a geopolitical battleground, failure to act decisively will only amplify the risks of disruption, coercion, and instability.

Cover image: Russian Sierra II-class submarine

Source: Eric B, “Postcards from Russia’s Frogmen”, https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2019/01/02/postcards-from-russias-frogmen/

[1] Galeotti, M., 2019. The Baltic States as Targets and Levers: The Role of the Region in Russian Strategy. George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/baltic-states-targets-and-levers-role-region-russian-strategy-0

Cormac, R. and Aldrich, R.J., 2018. Grey is the new black: covert action and implausible deniability. International Affairs, 94(3), pp.477–494. doi:10.1093/ia/iiy067.

[2] NATO (2023) Finland joins NATO as 31st Ally, NATO Newsroom. https://www.nato.int/cps/fr/natohq/news213448.htm?selectedLocale=en

NATO (2024) Sweden officially joins NATO, NATO Newsroom. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_223446.htm

[3] Decode39 (2023) ‘Why Moscow threatens the Med’s underwater domain’, Decode39, 31 May. Available at: https://decode39.com/6897/why-moscow-threatens-mediterranean-underwater-domain/

Calcagno, E. and Marrone, A. (2023) ‘The Italian approach to the underwater domain’, in The Underwater Environment and Europe’s Defence and Security. Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali, pp. 53-60.

[4] Ibidem

[5] Andžāns, Maris (2022) The Baltic Road to Energy Independence from Russia Is Nearing Completion, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 25 May. https://fpri.org/article/2022/05/the-baltic-road-to-energy-independence-from-russia-is-nearing-completion/

[6] These threats encompass supply manipulation – before becoming independent from the energy standpoint – and disruption, price hikes, disinformation campaigns, political pressure, and cyberattacks.

[7] World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) (2016) ‘Latvia Energy imports, net, in % of energy use 2006-2016’, World Bank. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/LVA/StartYear/2006/EndYear/2016/Indicator/EG-IMP-CONS-ZS

World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) (2013) ‘Latvia Fuels Imports by country and region in US$ Thousand 2013’, World Bank. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/LVA/Year/2013/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/all/Product/27-27Fuels

[8] Malmlof, T. (2011) ‘Baltic Energy Markets: The Case of Electricity’, in Nurick, R. and Nordenman, M. (eds.) Nordic-Baltic Security in the 21st Century: The Regional Agenda and the Global Role. Washington, DC: Atlantic Council.

[9] Syta, A. (2024) Baltic countries to leave joint power grid with Russia and Belarus, Reuters, 16 July. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/baltic-countries-leave-joint-power-grid-with-russia-belarus-2024-07-16/

[10] Monaghan, S. (2019) ‘Countering Hybrid Warfare: So What for the Future Joint Force?’, PRISM, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 82-98.

[11] Wallace, N. (2025) ‘Von der Leyen pledges solidarity after Latvia-Sweden undersea cable damage’, EURACTIV, 26 January. https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/von-der-leyen-pledges-solidarity-after-latvia-sweden-undersea-cable-damage/

[12] Reuters (2024) ‘Finland finds drag marks on Baltic seabed after cable damage’, Reuters, 29 December. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/finland-finds-drag-marks-baltic-seabed-after-cable-damage-2024-12-29/

[13] Thomas, M. and Maishman, E. (2022) ‘Nord Stream leaks: Sabotage to blame, says EU’, BBC News, 28 September. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63057966

Kottasová, I., Stockwell, B. and Murphy, P. P. (2024) ‘Two undersea cables in Baltic Sea disrupted, sparking warnings of possible “hybrid warfare”‘, CNN, 18 November. https://edition.cnn.com/2024/11/18/europe/undersea-cable-disrupted-germany-finland-intl/index.html

Braw, E. (2023) ‘A Pipeline Mystery Has a $53 Million Solution: Who sabotaged Finnish infrastructure—and was it war or not?’, Foreign Policy, 6 November. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/06/finland-pipeline-sabotage-balticconnector/

[14] Impelli, M. (2024) ‘Finnish Authorities Share Details About Russian Ship Suspected of Sabotage’, Newsweek, 30 December. https://www.newsweek.com/finnish-authorities-details-investigation-russian-ship-sabotage-2007597

[15] Praks, H. (2024) Russia’s hybrid threat tactics against the Baltic Sea region: From disinformation to sabotage. Hybrid CoE Working Paper 32. Helsinki: European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats.

[16] Gehringer, F. A. (2023) Undersea cables as critical infrastructure and geopolitical power tool: Why undersea cables must be better protected. Facts & Findings No. 495. Berlin: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/22161843/Undersea+cables.pdf/aee8e59b-96dc-bc05-18ac-b1070eb76bc1

[17] Quinville, R. S., Moyer, J. C.,; Lindholm, R. (2024) ‘Risky Game: Hybrid Attack on Baltic Undersea Cables’, Wilson Center, 25 November. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/risky-game-hybrid-attack-baltic-undersea-cables

[18] This is also dubbed as “whole-of-society approach” or “Comprehensive security approach”

[19] Terry, G. S. (2024) ‘Responsibilising Total Defence: Interrogating Resistance, Resilience, and Agency in Finland, Sweden, and Lithuania’, Journal on Baltic Security, 10(2), pp. 26-51. doi:10.57767/jobs_2024_012

[20] DEMIFIL: diplomatic, economic, military, informational, financial, intelligence, and law enforcement

Elonheimo, T. (2021) ‘Comprehensive Security Approach in Response to Russian Hybrid Warfare’, Strategic Studies Quarterly, pp. 113-137.

[21] NATO(2024) ‘NATO officially launches new Maritime Centre for Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure’, NATO Media Centre, 28 May. https://mc.nato.int/media-centre/news/2024/nato-officially-launches-new-nmcscui

[22] Westgaard, K. (2023) ‘The Baltic Sea Region: A Laboratory for Overcoming European Security Challenges’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 21 December. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/12/the-baltic-sea-region-a-laboratory-for-overcoming-european-security-challenges?lang=en

[23] Opitz, C. (2015) Potential for Nordic-Baltic Security Cooperation: Shared Threat Perception Strengthens Regional Collaboration, SWP Comments 40, August. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP).

[24] Sweden no longer officially uses the term neutrality after joining the European Union in 1995. However, neutrality and non-alignment are typically regarded as synonymous in the Nordic context.

[25] Westgaard, K. (2023) ‘The Baltic Sea Region: A Laboratory for Overcoming European Security Challenges’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 21 December. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/12/the-baltic-sea-region-a-laboratory-for-overcoming-european-security-challenges?lang=en

[26] Marine Technology News (2025) ‘Private sector to help protect subsea cables in Europe’, Marine Technology News, 16 January. https://www.marinetechnologynews.com/news/private-sector-protect-subsea-644296

[27] Westgaard, K. (2023) “The Baltic Sea Region”

Mergener, H.-U. (2024) ‘Germany and Norway push for improved protection of critical underwater infrastructure’, European Security & Defence, 21 October https://euro-sd.com/2024/10/major-news/40957/underwater-infrastructure/ Six North Sea countries (2024) Joint Declaration on cooperation regarding protection of infrastructure in the North Sea, 9 April.

Chiappa, C. (2024) ‘6 countries move to protect the North Sea from Russians’, POLITICO, 9 April. https://www.politico.eu/article/6-european-countries-sign-pact-protect-critical-energy-infrastructure-north-sea-from-russia/

[28] In addition to the expansion of joint capabilities and structures, the revitalized NORDEFCO is to focus primarily on joint defense planning and preparations for conducting joint operations. In 2015, the NORDEFCO Cyber Warfare Collaboration Project (CWCP) has been established to collaborate with the Estonia-based NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence

[29] Besch, S. and Brown, E. (2024) Securing Europe’s Subsea Data Cables. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 16 December. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/12/securing-europes-subsea-data-cables?lang=en

[30] NATO (2022) NATO 2022 Strategic Concept: Adopted by Heads of State and Government at the NATO Summit in Madrid 29 June 2022. Brussels: North Atlantic Treaty Organization. https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept

[31]European Commission (2023) Joint communication on the update of the EU Maritime Security Strategy and its Action Plan: An enhanced EU Maritime Security Strategy for evolving maritime threats. Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. Available at: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/publications/joint-communication-update-eu-maritime-security-strategy-and-its-action-plan-enhanced-eu-maritime_en

EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region (EUSBSR) https://eusbsr.eu/

[32] European Commission (2024) Commission Recommendation (EU) 2024/779 of 26 February 2024 on Secure and Resilient Submarine Cable Infrastructures. Official Journal of the European Union, L 2024/779, 8 March. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2024/779/oj

[33] Dudzińska, K. (2025) ‘Acute Need for Security of Critical Infrastructure in the Baltic Sea Region’, Polish Institute of International Affairs, 16 January. https://pism.pl/publications/acute-need-for-security-of-critical-infrastructure-in-the-baltic-sea-region

[34] NATO(2024) ‘NATO officially launches new Maritime Centre for Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure’, NATO Media Centre, 28 May. https://mc.nato.int/media-centre/news/2024/nato-officially-launches-new-nmcscui

[35] NATO (2024) ‘Joint Expeditionary Force trains protecting critical undersea infrastructure’, NATO Newsroom, 6 June. https://ac.nato.int/archive/2024/JEF_nordic_warden_24

[36] NATO (2025) ‘NATO launches “Baltic Sentry” to increase critical infrastructure security’, NATO Newsroom, 14 January. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_232122.htm

* Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance

[37] Lange, H., Combes, B., Jermalavičius, T. and Lawrence, T. (2019) To the Seas Again: Maritime Defence and Deterrence in the Baltic Region. International Centre for Defence and Security.

[38] HELCOM and VASAB (2023) Work plan of the Joint HELCOM-VASAB Maritime Spatial Planning Working Group for 2022-2024. HELCOM and VASAB. https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/HELCOM-VASAB-MSP-WG-Work-Plan-2022-2024_approved-by-VASAB-and-HELCOM_simplifyfied-for-web.pdf

Metrick, A. and Hicks, K.H. (2018) Contested Seas: Maritime Domain Awareness in Northern Europe. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, Center for Strategic & International Studies.

[39] NATO (2025) ‘NATO launches “Baltic Sentry” to increase critical infrastructure security’, NATO Newsroom, 14 January. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_232122.htm U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa (2023) BALTOPS 23: Strengthening Combined Response Capabilities in the Baltic Sea. https://c6f.navy.mil/Press-Room/Image-Gallery/igphoto/2003241990

The Maritime Executive (2024) NATO Wants to Use Drone Boats for Maritime Security in the Baltic. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/nato-wants-to-use-drone-boats-for-maritime-security-in-the-baltic

Robertson, N. and Dean, S. (2025) ‘Ships, sea drones and AI: How NATO is hardening its defense of critical Baltic undersea cables’, CNN, 27 January. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/01/27/europe/nato-defense-baltic-undersea-cables-intl-cmd/index.html

Soldi, G., Gaglione, D., Raponi, S., Forti, N., d’Afflisio, E., Kowalski, P., Millefiori, L. M., Zissis, D., Braca, P., Willett, P., Maguer, A., Carniel, S., Sembenini, G. and Warner, C. (2023) Monitoring of Underwater Critical Infrastructures: The Nord Stream and Other Recent Case Studies. arXiv https://arxiv.org/pdf2302.01817

Shuja, S. F. (2024) ‘Beneath the surface: The strategic implications of seabed warfare’, Daily Sabah, 3 December. https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/op-ed/beneath-the-surface-the-strategic-implications-of-seabed-warfare Luhtala, H., Erkkilä-Välimäki, A., Eliasen, S.Q. and Tolvanen, H. (2021) ‘Business sector involvement in maritime spatial planning – Experiences from the Baltic Sea region’, Marine Policy, 123 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104301

[40] Dark Shipping, 2024. Fusing AIS Data and SAR to Enable Global Monitoring of Dark Vessels. https://darkshipping.com/solutionsexpanded/fusing-ais-data-and-sar-to-enable-global-monitoring-of-dark-vessels

Bae, I. and Hong, J., 2023. Survey on the Developments of Unmanned Marine Vehicles: Intelligence and Cooperation. Sensors, 23(10), https://doi.org/10.3390/s23104643

Pohonțu, A., 2020. A Review over AI Methods Developed for Maritime Awareness Systems. Scientific Bulletin of Naval Academy, Vol. XXIII, pp.287-299. https://www.anmb.ro

[41] Magnuson, S. (2024) ‘NATO Summit News: Baltic Sea now called a ‘NATO Lake’’, National Defense Magazine, 10 July. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2024/7/10/baltic-sea-now-called-a-nato-lake

[42] Terna (2024) ‘The “underwater” domain: the new global race is played out in the ocean depths’, Lightbox, 7 September. https://lightbox.terna.it/en/transition/underwater

Spagnol, G. (2024) Geopolitics of the Mediterranean. Institut Européen des Relations Internationales https://ieri.be/fr/publications/wp/2024/f-vrier/geopolitics-mediterranean

[43] Calcagno, E. and Marrone, A. (2023) ‘The Italian approach to the underwater domain’, in The Underwater Environment and Europe’s Defence and Security. Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali, pp. 53-60.

[44] European Union (1995) Barcelona Declaration, adopted at the Euro-Mediterranean Conference, 27–28 November 1995, Barcelona. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/

[45] International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) (2023) Turbulence in the Eastern Mediterranean: Geopolitical, Security and Energy Dynamics. November. IISS. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/strategic-dossier-preview-turbulence-in-the-eastern-mediterranean/

[46] Ibidem

[47] Mainas, E. (2011) ‘Maritime surveillance and policing – integrated and coordinated?’, in G. Merritt (ed.) Maritime security in the Mediterranean: Challenges and policy responses. Brussels: Security & Defence Agenda, p. 14.

[48] Paik, A. and Counter, J. (2024) ‘International law doesn’t adequately protect undersea cables. That must change.’, Atlantic Council, 25 January. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/hybrid-warfare-project/international-law-doesnt-adequately-protect-undersea-cables-that-must-change/

[49] UNEP/MAP (n.d.) The blue economy in the Mediterranean. https://www.unep.org/unepmap/resources/factsheets/blue-economy

Bravo Villa, C., Folegot, T., Pimentel, V., Weilwart, L. & Entrup, N. (2024) Analysis of maritime traffic speed in 2023 in the NW Mediterranean PSSA: establishing a baseline to monitor progress in complying with IMO recommendations for speed in the PSSA. ACCOBAMS-SC16/2024/Doc18. https://accobams.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SC16.Doc18_Analysis-of-maritime-traffic-speed-in-2023-in-the-NW-Mediterranean-PSSA.pdf

[50] West, L. (2024) ‘Thales leading SEACURE seabed defence project’, UK Defence Journal, 30 December. https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/thales-leading-seacure-seabed-defence-project/

[51] Gosselin-Malo, E. (2024) ‘NATO drill sends divers, drones to sneak by underwater alarm sensors’, Defense News, 15 November. https://www.defensenews.com

[52] NATO Allied Command Transformation (2025) ‘NATO’s Mainsail: Enhancing the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure through Advanced Data Exploitation’, NATO ACT, 21 January. https://act.nato.int/article/natos-mainsail/

[53] NATO Allied Command Transformation (2025)‘NATO TASK FORCE X: Deterring Today and Protecting Tomorrow’, NATO ACT, 31 January https://act.nato.int/article/nato-task-

[54] NATO (2024) Individually Tailored Partnership Programmes. https://www.nato.int/cps/bu/natohq/topics_225037.htm

[55] NATO (2024) Partnership Interoperability Initiative. https://www.nato.int/cps/cn/natohq/topics_132726.htm

[56] Nicolò Fasola, “Reforming and Enhancing Partnerships to Strengthen NATO’s Strategic Posture,” Parameters 54, no. 4 (2024), doi:10.55540/0031-1723.3319.

[57] PESCO website: Projects, https://www.pesco.europa.eu

[58] Reuters (2025) ‘TIM sets new deadline of March 15 for Sparkle sale’, Reuters, 22 January. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/tim-extends-march-15-exclusivity-period-sparkle-bid-italy-treasury-asterion-2025-01-22/

[59] Submarine Telecoms Forum, “Industry Report, 2024–2025: Issue 13,” 94