Abstract

Libya is one of the World’s most arid countries. To provide a reliable water supply to its citizens, its government has decided to tap directly into the largest known underground water basin: the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, located under Libya, Egypt, Chad and Sudan. The resulting network of pipelines and wells is better known as the Great Man-Made River; it is the result of a herculean effort and it did manage to help Libya overcome part of its structural water issues. However, after more than fifty years of planning and construction, this project has essentially ground to a halt because of Libya’s current geopolitical situation and because of the passing of Muammar Gaddafi, its greatest contributor. What will happen to Libyans and their water, if the internal political context will not deliver some much-needed stability? What will Libya’s neighbours think of the project once completed?

Introduction

Most of the world’s biggest and oldest cities are located near rivers, seas, oceans or other bodies of water. Libya’s population distribution reflects this pattern. To understand this nation, it is crucial to know that Libya is one of the very few nations in the world without any permanent natural rivers. The very few seasonal rivers which form during heavy rainfall (wadis, from the original Arabic) are simply not enough to sustain a stationary civilisation due to their ephemeral and unpredictable nature. Countries in the MENA Region (Middle East and North Africa) are often associated with desertic and arid imagery, but nowhere is this as true as it is for Libya. Historically, Libya’s stable population centres have been situated on its Mediterranean coast, where they could access trade routes and, crucially, where they could access replenishable aquifers and some millimetres of yearly rainfall.

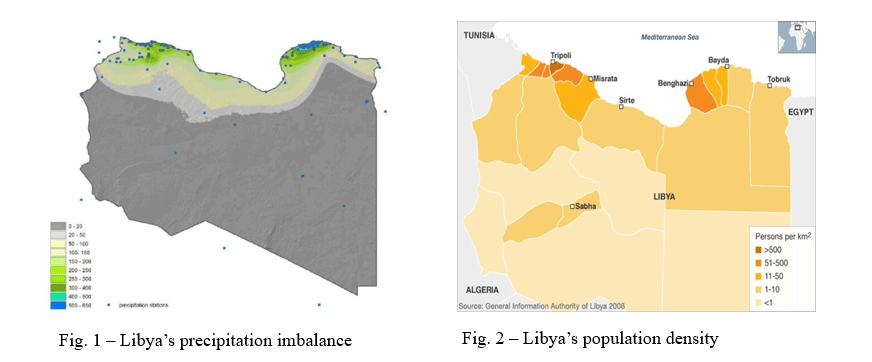

Comparing figs. 1 and 2, even at a quick glance, reinforces this thesis. Libya’s hinterland is one of the most inhospitable places on Planet Earth, being entirely engulfed by the sandy Sahara Desert. However, the utter and absolute lack of surface water does not translate into Libya’s hinterland being completely dry. Geological studies have highlighted that, as recently as 9000 to 4000 years ago, the area which now hosts the Sahara Desert had a humid climate and stable vegetation patterns.[1] The water necessary to support all this life did not disappear during the desertification of this area; it is still located there, albeit deep underground.

In fact, Libya’s hinterland is directly above the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, the largest underground aquifer of its kind in the world, estimated to be anywhere between 10.000 to 1.000.000 years old, 4km deep and 1.5 million large, with various periods of expansion and retraction during the morphological history of the Sahara.[2] The first wells were discovered during the 1950s; since then, the Libyan government has tried to make use of them and bring their precious water to its northern population centres by constructing a vast network of drills, pipelines and reservoirs: the Great Man-Made River Project (GMRP).

Historical Perspectives of the GMRP

Conducting an overview of the GMRP without mentioning its creator would be impossible. Muammar Gaddafi has been a deeply controversial figure, although it is undeniable that the stability of his regime and his unwavering commitment to the GMRP have been crucial to its development. Throughout this article, some of Libya’s main historical events over the last 70 years will be mentioned; for the purpose of brevity and conciseness, they will not be explored in their entirety but only in their relation to the GMRP.

In 1959, Libya found vast oil deposits in the areas of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania. Ten years later, due to a combination of long-term economic factors and short-term instability in the region, the Libyan King Idris was deposed by the Officers’ Coup and Muammar Gaddafi gained control of the Libyan government.[3] Explorations both pre- and post-revolution, aimed at finding oil reserves beneath the Sahara, actually encountered the first pockets of what would then be recognised as the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System.

Acknowledging the potential of such a discovery, Gaddafi used most of the revenue from the nationalisation of the petroleum companies – and the subsequent rise in the price of crude oil – to dig more wells and establish large farms on the now-arable southern part of Libya. However, this initial approach failed. Many people were reluctant to move to what had been an inhospitable desert wasteland just a few months prior; thus, the approach had to change. The efforts of the government were now directed towards bringing the much-needed water to the northern settlements: the seeds of the GMRP were sown.[4]

The initial feasibility studies were conducted in the early 1970s, just as the strain on the existing Libyan water supply was heightened by the rapid economic development and saltwater was beginning to seep into the coastal aquifers due to over-depletion. In 1983, Laws no. 10 and 11 of the General Peoples Congress were passed, establishing the managing authority for the GMRP (The Man-Made River Authority, MMRA) and allocating the funds necessary for the project.[5]

Given Gaddafi’s increasing isolation from other countries in the Western bloc, all the money needed for the project was supplied by the Libyan government without any sort of international investment or aid. Taxes were levied on cigarettes, air travel and other sorts of “luxury goods” (at one point, even imported bananas fell under this category).[6] Although the official website of the MMRA provides a figure of 12 billion Libyan dinars (approximately $2 billion), other sources estimate the total cost of the GMRP to be closer to 20-30 billion USD.[7]

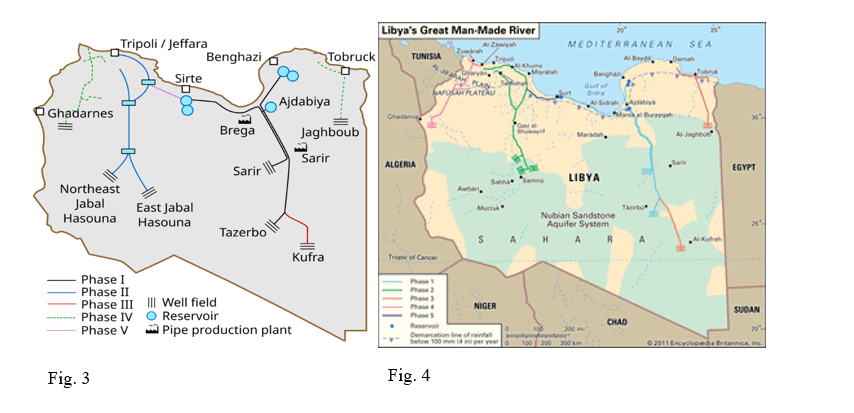

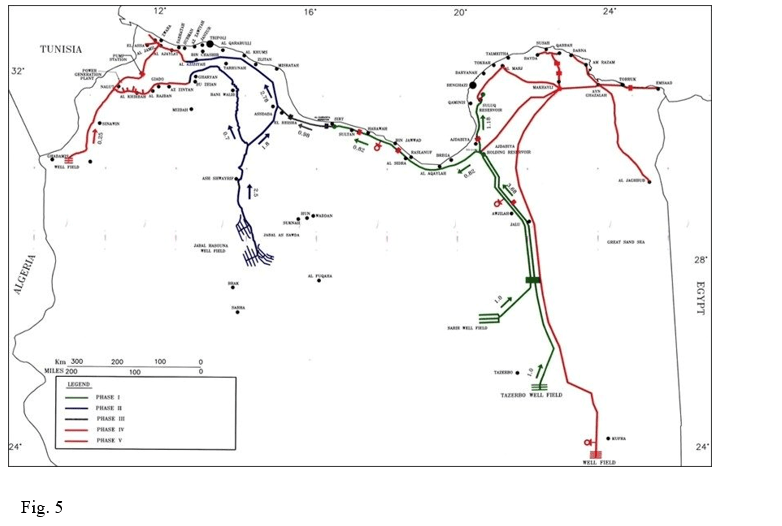

The project was divided into five main phases, all of them specifying which section of the total network was to be built and for what purpose. Phase I consisted in building two wellfields in Sarir and Tazerbo to obtain water from the Kufra-Sarir basin, in the South-Eastern part of the country. The water, designed to flow at a rate of 350 million per year from each wellfield, is directed towards the coastal cities of Benghazi and Sirte (from Tazerbo and Sarir, respectively).[8] Worthy of note are also the various infrastructural networks that were put in place to support the creation of this phase: a reservoir in the city of Ajdabiya, tasked with preserving some of the water in the event of a drought; a pipe manufacturing plant at Brega, which is the main producer of the 4-metre diameter, 7-metre long, steel-reinforced pre-stressed cement pipes used to transport the water; a 1500 km road along the structure of the pipeline in order to rapidly transport the equipment and materials necessary for maintaining the network.[9] This phase was completed and inaugurated in the 1990s. The partial beginning date was 1993, with the Phase reaching full power in 1996.

Phase II set to build the largest wellfield of its kind in history, operating 484 wells over an area of more than 19 thousand square kilometres.[10] This area in Jabal Hassouna obtains its water from the Muzuq-Hamada basin, which is closer to the Western Sahara Aquifer System rather than the Nubian Sandstone one. The total flow of water, directed to Tripoli and other settlements on the Jifarah plain, is 900 MCM/Y. A combination of instability in Libya in the late 1990s, competitive tendering of the planned seven parts of the phase, financial stresses due to a fall in governmental revenue led to a change in the contractor company and a generalised delay in the construction process. Phase II became operational in 1999.[11]

Phase III consisted of a link between the first two phases of the GMRP, enabling a bi-directional flow of water and connecting the two most significant strands of the network. This was done via an enlargement of the western branch of Phase I, connecting to Sirte. Phases IV and V, severely delayed by the 2011 Revolution and the ensuing civil conflicts which followed Gaddafi’s fall, would have included other pipelines in the far western corners of the country, from the area around Ghadarnes to the coastal cities west of Tripoli. Phase V of the GMRP aimed to reinforce the flow of water of Phase I via a supplementary 380 km pipeline and another wellfield in Kufra, in the south-east, and extend the water supply to the north-easternmost part of the country around the city of Tobruk.

Many sources often contradict each other on which particular strands of the network actually constitute Phases III, IV and V; this is probably due to the incompleteness of the project and the lack of a clear timeframe, as opposed to the relatively swift and efficient order of Phases I and II which allowed them to be classified more easily.[12] As per the time of writing, February 2025, it can be stated that only three fifths of the total project are completed and operational. Figs. 3, 4, and 5 have been included to show examples of contradicting evidence on which sections of the GMRP account for which phases.

Political and Economic Perspectives of the GMRP

The Great Man-Made River, for all intents and purposes and by all the most common definitions, can be classified as a mega-project.[13] The organisational and managerial issues which have plagued its deployment, largely due to factors exogenous to the GMRP’s management, such as a regime change, direct military attacks on the infrastructure and a vicious civil war where separate factions control different areas of the territory – with sections of the GMRP potentially disconnected from one another – are all notable factors of its existence as well. The political perspectives of the GMRP worthy of note mostly revolve around Libya’s international standing post-GMRP. It is an undeniable policy success on the domestic front: providing fresh water to millions of people in a barren desert is nothing short of a miracle; on the international front, issues of overreliance and trans-border management will prove crucial to adequately coordinate in the future. Internally, the fundamental political aspect to truly consider is the civil war’s effect on the project’s management and its vulnerabilities. Economically, the GMRP raises questions of sustainability, in both the environmental and monetary sense.

Politics

Starting with addressing the political nuances of such a project, it must be acknowledged that the GMRP was merely a choice that the Libyan government made during the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, while Libya had the natural resource potential that made the GMRP theoretically possible, it could also have decided to import water from other countries or heavily invest in desalinisation plants. Both of these options were eventually discarded.

The first one is obvious dependence and vulnerability issues: relying on a foreign actor to supply a population with its most vital resource would essentially mean relinquishing the political control to them; being that dependent on another nation is uncommon and generally disadvantageous. The true choice that the Libyan government had to make was whether to proceed with the implementation of the GMRP or with an expansion of their desalinisation facilities.[14] For economic reasons which will be explored later, they went with the former. This meant that they were, and still are, confined to get their water from a single source; as stated in the previous section, the coastal aquifers are simply insufficient to support all of Libya’s present population and economic activity.[15]

What the ongoing civil war has shown is that even a handful of well-coordinated rebels can sabotage the whole network by capturing strategic points: in 2019, a platoon of rebels occupied a water management station near Tripoli, encompassed in the Phase II network, and cut off the capital’s water supply for several days.[16] The situation eventually de-escalated, but it was a grim alarm for a situation that might very well happen again in the near future. To that, it must also be added that the GMRP needs expensive and careful maintenance interventions, which are of course impossible in times of war or even governmental uncertainty. Internally, the single biggest challenge that the GMRP will have to face will be finding a stable government, no matter its aims or political orientations. Without it, its existence and all Libyans’ water access will be threatened.

The GMRP has also caused a number of international headaches, both directly and indirectly. During the 2011 revolution and ensuing conflicts, a NATO bombing of the Brega pipe manufacturing plant severely damaged its production capabilities, thus hindering the progress for the phases which were not yet built and preventing existing pipes to be substituted. The justification behind this attack was that the Brega plant was being used as a secret military missile-launch site.[17]

At this point, it is important to notice that different nations within the Wider Mediterranean “belong” to different areas of influence; the traditionally Western allies and the more detached nations in MENA and the wider Arab world reported this story and the underlying narrative in opposite ways.[18] What remained of the attack was a crippled GMRP, regardless of the intention behind it. Relatively recent interviews from Libyan sources have reported the closure of 101 wells from Phase II of the GMRP.[19]

Indirectly, the main point of concern is that both the Aquifer Systems from which the GMRP gets its water do not fully fall under Libya’s jurisdiction. The North-Western Sahara Aquifer System (NWSAS) is shared by Libya, Tunisia and Algeria, while the already cited Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (NAS) is shared by Libya, Egypt, Chad and Sudan.[20] According to basic International Law, all of these countries should have a stake in the management and extraction process of the resources contained in these Aquifers; in reality, some are more developed than others regarding the infrastructure needed for such extraction.

The NWSAS is the more threatened of the two aquifers: continued extraction from all the countries could have meant an exhaustion of the water resources, a disappearance of the artesian wells and a general worsening of the quality of the water extracted. This situation led to the creation of a new authority under the general oversight of the Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS, an acronym from the original French), which would coordinate the management of this trans-border resource and establish extraction quotas for each of the parties involved.[21]

For the NAS, the four concurrent countries have created a Joint Management Authority which has seen full participation since 1999.[22] However, two extremely demanding projects have been built by relying on this basin: the already cited GMRP, especially its eastern Phases, and the Egyptian East Owainat project, aiming to make the desertic lands in the western part of the country, far away from the Nile, fertile.[23] The water extracted from the NAS is used to irrigate large swaths of terrain via central-pivot circular sprinklers. Coordinating these two projects in managing the common resource they depend on will be crucial for their continued success and the welfare of both countries’ populations. It can be a virtuous example of how to manage a precious resource in a scarce environment.

Economics

The two biggest aspects of the GMRP to consider on the economic side are the reasoning behind its implementation and its sustainability. As stated above, when faced with the chronic water shortage and increasing demand, Libyan planners had a blank canvas upon which to move. They chose to study, devise and implement the GMRP, but they could have just as easily expanded their already existing desalinisation network. Libya has turned to desalinisation as a way to provide water for their population since the 1960s.[24] They were not alone in that: during those same years another relevant actor within the Wider Mediterranean, faced with a similar problem, decided to implement desalinisation plants which are now considered state-of-the-art: Israel. Therefore, when faced with an ever-growing demand for water, planners decided to build the infrastructural network which would have delivered the largest quantity of water at the smallest possible cost per unit.

Even though most of this article has referred to the coastal settlements as the largest beneficiaries of the GMRP, this does not necessarily mean that the bulk of the water is reserved for residential usage. In fact, according to the MMRA itself, the majority of the water is actually used for agricultural and irrigation purposes, with industrial water closing the list as the least thirsty sector in Libya.

Estimates of water cost per cubic metre before the construction of the process and after its first phases gave an edge to the GMRP. During the conception of the project, the first estimates returned a predicted cost of 0.25 US$ per cubic metre of water supplied by the GMRP, compared to the much costlier 2-3 US$ per cubic metre that an expansion of the desalinisation network would have brought.[25] Future estimates continued to justify the investment that the Libyan government poured into the GMRP.

In the 1990s, evidence from three studies expressed in the local currency placed the cost for GMRP water at 0.05 to 0.30 Libyan Dinars per cubic metre, depending on periods of high and low demand, respectively (if the market exchange rate is to be considered more accurate than the official one, these figures are 0.02 to 0.10 US$). Estimates for desalinated water ranged from 0.3 to 0.4 LD/ under the governmental exchange rate of US$ to 2.7 to 3.9 LD/

under the market exchange rate (approximately 0.9 to 1.3 US$).[26] More recent estimates, dating to 2007, placed the real estimated cost of GMRP water for 2020 at 0.7 LD

, almost doubling from the 1996 estimates.[27] Prior to the generalised collapse of the system in 2011, water was subsidised and sold for 0.15 US$/

.[28][AB1] [DP2]

All these figures go to show that water in Libya, despite being a rare and valuable substance, is almost paradoxically cheap, especially when compared to other MENA countries or even countries such as the Netherlands, which reflect both the cost of the resource and all the fixed and variable costs needed for the upkeep of the infrastructure.[29] This is one of the ways in which the GMRP might not be sustainable in the long term unless steps are taken. The other obvious risk factor is that all the aquifers upon which the GMRP depends are fossil and non-replenishable.

However, while the political institutions created for the management and development of these areas have been mentioned above, this does not change the fact that the water contained in both aquifers cannot be used more than once. The NAS especially is particularly interesting, as it is a hydrological body of “known unknowns”: due to its sheer size and depth, nothing more accurate than computer simulations could be surveyed; therefore, not everything is known in detail about the volume of water that the NAS contains, the direction of its internal flows and its various ramifications, though the science on the topic is progressing at a fast pace.[30]

For Libyans, thus, relying solely on the GMRP could prove risky. Due to the generalised uncertainty about the NAS’ specifics, nobody can predict with rigour the length of time by which the current rates of extraction by all the operating plants can be maintained. While some sensationalistic press articles claim that the water in the NAS is enough to last all four sharing countries for more than 800 years, other sources instead claim that the volume of water extracted by the GMRP alone would doom the aquifer and consume all of its water by the end of the 21st century.[31]

Either way, both aquifers have an expiration date, though imprecise. What is certain is that without an expansion of their desalinisation infrastructure, Libyans will be doomed to risk their water supply whenever there is a conflict or should the GMRP fail for lack of the necessary maintenance. All the necessary considerations as to what an expansion of Libyan desalinisation would mean for the Mediterranean Sea as an ecological and hydrological basin, and to all the other countries which depend on it for their existence and economic wellbeing, must be also made carefully.

Conclusion

This brief excerpt on the Great Man-Made River Project hoped to provide some perspectives to a wider audience on how Libyans get their water and manage it. The GMRP is nowhere near completion and full utilisation: all major construction has stopped since 2011, with many damages to the infrastructure being registered since then. For the future, it will be essential to regain the governmental stability necessary to the GMRP’s past development. For Libya, a reliable water supply will be the fruit of successful international cooperation with other countries in the MENA and Wider Mediterranean regions. Managing the deep aquifers in their hinterland and cultivating good relations with the neighbouring countries with which they share them will be essential in preventing the likely water wars that could arise in the region in the future.

Cover image: Transport of pipe segments in the 1980s, Wikipedia

Fig. 1: DOI: 10.5829/idosi.larcji.2012.3.6.1112

Fig. 2: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.045

Fig. 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Man-Made_River#/media/File:Great_Man_Made_River_schematic_EN.svg

Fig. 4: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Man-Made-River

[1] Ait-Brahim, Yassine. “When the Sahara Grew Green: Constraining the ‘Green Sahara’ Across Time and Space” Scientia: Earth and Environmental Sciences, January 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.33548/SCIENTIA1164

[2] Ait-Brahim, “Green Sahara”; Hosseini, Zohreh et al. “Comprehensive hydrogeological study of the Nubian aquifer System, Northern Africa” Journal of Hydrology 636, (2024): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131237

[3] According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, those factors were, respectively, the hyper-reliance on foreign companies to extract and manage the newly discovered oil and the failure of the King to denounce Israel after the June War of 1967. Encyclopaedia Britannica (2025) ‘History of Libya’. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Libya/History

[4] Encyclopaedia Britannica (2023) ‘Great Man Made River’. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Man-Made-River

[5] “History and Evolution of GMMR”, About GMMR, Man Made River Authority, Copyright 2025. Available at: https://gmra.com.ly/index.php/en/about-gmmr/history-and-evolution-of-gmmr

[6] Fetouri, Mustafa. “NATO’s Intervention Threatens Libya’s Unique Man-Made River” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, June 9, 2023. https://www.wrmea.org/north-africa/natos-intervention-threatens-libyas-unique-man-made-river.html

[7] Altaeb, Malak. “What’s next for Libya’s Great Man-Made River Project?” Middle East Institute, August 10, 2022. https://www.mei.edu/publications/whats-next-libyas-great-man-made-river-project

[8] MCM/Y is the unit of measurement used by most sources and by the MMRA itself; for the sake of consistency, whenever this article will refer to “million cubic metres per year” it will align with this nomenclature.

[9] Byrnes, Kelly P., “Freshwater management in Libya: a premonition of the global water crisis” Master’s Thesis, University at Albany, State University of New York, 2013. Legacy Theses and Dissertations 2009-2024. 845.

[10] Abdudayem, Abdulmagid and Scott, Albert H.S. “Water infrastructure in Libya and the water situation in agriculture in the Jefara region of Libya” African J Economic and Sustainable Development 3, no. 1 (2014), 33-64, 56.

[11] Byrnes, “Freshwater Management”, 36.

[12] Examples of contradicting sources for the numbering of the last three Phases: Byrnes, “Freshwater management”, 36-37; Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Great Man Made River”; Alghariani, S.A. “Man-Made Rivers: A New Approach to Water Resource Development in Dry Areas” Water International 22 (1997), 113-117, 116; Maiar, Salem. “Libya prepares final phase for giant man-made river” AGBI, December 2, 2024. Available at: https://www.agbi.com/opinion/infrastructure/2024/12/libya-prepares-final-phase-for-giant-man-made-river/

[13] For the definition and operationalization of the concept of “Megaproject”, cfr. Bakke, Christian and Johansen, Agnar. “Which attributes define a megaproject?” IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 1389 (2024). doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1389/1/012029

[14] Gijsbers, P.J.A. and Loucks, D.P. “Libya’s Choices: Desalinization or the Great Man-Made River Project” Phys. Chem. Earth (B) 24, no.4, (1999), 385-389. PII: s1464-1909(99)00017-9

[15] Alghariani, “New Approach to Water Development”, 116

[16] Haftar, Khalifa. “Libya armed group cuts off water supply to Tripoli” Aljazeera, May 21, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/21/libya-armed-group-cuts-off-water-supply-to-tripoli

[17] Byrnes, “Freshwater Management”, 39.

[18] Byrnes, “Freshwater management”, 39; Mathaba. “Libya’s “Water Wars” and Gaddafi’s Great Man-Made River Project” GlobalResearch, May 13, 2013. https://www.globalresearch.ca/libyas-water-wars-and-gaddafis-great-man-made-river-project/5334868

[19] The original interview was given in 2019, by Abdullah El-Sunni to the news agency Reuters. Cameron, Hugh. “World’s Biggest Man-Made River Hits Hurdles in $25 Billion Project” Newsweek, Aug 28, 2024. https://www.newsweek.com/worlds-largest-man-made-river-1944773

[20] A schematic map of the two aquifers and their ranking with other World basins available at: https://books.gw-project.org/large-aquifer-systems-around-the-world/chapter/differences-in-size-small-and-large-aquifers-aquifer-systems/

[21] Benidris, Abdallah Mohamed and Kumati, Mohamed Omar “Managing Transborder of Groundwater Basin in Great Man-Made River Authority – Libya” Journal of Global Resources 2, (2016) 159-170; cfr. also Sahara and Sahel Observatory OSS The North Western Sahara Aquifer System: Concerted management of a transboundary water basin (Synthesis Collection no.1, 2008), ISBN : 978-9973-856-30-2

[22] CEDARE (2014), “Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (NSAS) M&E Rapid Assessment Report”, Monitoring & Evaluation for Water In North Africa (MEWINA) Project, Water Resources Management Program, CEDARE.

[23] National Company for Land Reclamation & agriculture in East Owainat, “About Company”. http://www.nspo.com.eg/nspo/ar/Awenat/index.html

[24] Brika, Bashir “The water crisis in Libya: causes, consequences and potential solutions” Desalinisation and Water Treatment 167, (2019), 351-358. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2019.24592

[25] Alghariani, “New Approach to Water Development”, 117

[26] Gijsbers and Loucks, “Libya’s Choice”, 387

[27] Elhassadi, Abdulmonem “Libyan National Plan to resolve water shortage problem Part Ia: Great Man-Made River (GMMR) project — capital costs as sunk value” Desalinisation 203, no. 1-3, (2007) 47-55, 51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2006.05.003

[28] “Water Scarcity and Climate Change: an analysis on WASH enabling environment in Libya”, UNICEF Libya, published September 2022, https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/19321/file/Libya%20water%20scarcity%20analysis%20and%20recommendations_%20UNICEF%20Sep%202022.pdf

[29] Ibid.

[30] Wood, Cara. “The Water Is Ancient, The Secrets Are Many” IAEA, March 22, 2010. https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/water-ancient-secrets-are-many; cfr. Hosseini et. Al. “Comprehensive hydrogeological study”

[31] Abebe, Tesfu Telahun. “The floating Sahara, Egypt’s obsession with perpetual dependency”, New Business Ethiopia, March 9, 2020. https://newbusinessethiopia.com/nbe-blog/the-floating-sahara-egypts-obsession-with-perpetual-dependency/ ; Topol, Sarah A. “Libya’s Qaddafi taps ‘fossil water’ to irrigate desert farms” The Christian Science Monitor, August 23, 2010. https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2010/0823/Libya-s-Qaddafi-taps-fossil-water-to-irrigate-desert-farms/%28page%29/2