Submitted: 7 October 2024

Abstract

In the past years, the protection and strengthening of submarine cables have become a primary objective for the European Union. However, up until today, regulatory e↵orts have mostly focused on building resilience against malicious attacks from third parties. More recently, the securitisation of submarine cables has gained a new dimension as the Union has realised the potentially harmful consequences of internal threats originating from cable providers. The case behind the construction of the SEA-ME-WE 6 and EMA cables has shown how internal breaches of information or disruption of communication could become a serious risk in the future. As a result, we argue that current EU policies have delineated a response against external attacks but are not yet ready to protect submarine infrastructure against internal threats. This paper recommends the formulation of a unitary policy on the matter of cable security, together with an increased resilience against potential malicious partners such as China through better risk assessments, more stringent investment regulations, thorough analyses of cable providers, and improved control on Foreign Direct Investments. Overall, these recommendations fall under the more general and long-term strategic objective of acquiring more data sovereignty in the context of the European Union.

Introduction

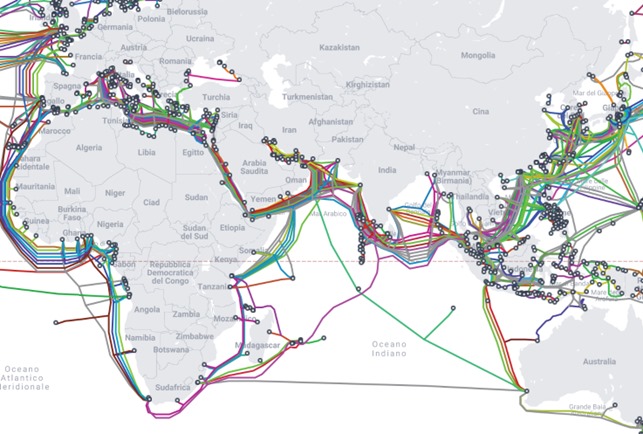

In recent times, security threats against submarine cables have become a source of great concern for both regional and national actors. As of 2024, there are already 600 submarine cables connecting the world. Of these, 70 routes are in the process of being constructed or renovated.[1] Moreover, it is estimated that almost 99% of global data traffic travels through submarine cables, making them one of the most vulnerable infrastructures of current geopolitics. Attacks on submarine cables can lead either to the disruption of data transmittance or the interception of valuable information. In both cases, whether it means gaining access to sensible intelligence or blocking the normal functioning of everything from emails to bank transactions, the securitisation of this marine infrastructure will surely play a fundamental role in the future of geopolitics.

Very recently, the securitisation of submarine cables has gained a new dimension. Rather than building resilience only against external attacks, the international community has become fearful of internal threats originating from cable providers. More specifically, there are rising concerns that companies owned by strategic competitors such as China might be responsible for the interception of data or the disruption of these infrastructures in the pursuance of geopolitical interests. In the past years the European Union focused solely on malicious attacks from third parties and has only recently begun facing this issue. As a result, we argue, the EU is still lacking the necessary policies to protect and strengthen its submarine infrastructure against internal threats.

This policy paper will begin by considering the development of this issue, especially by analysing the growth of HMN Technologies Co. Ltd. in the cable sector and the recent case of the SEA-ME-WE 6. We will highlight the rising competitiveness between cable providers and its security implications. Secondly, we will consider current EU policies on submarine cable security, highlighting along the way their shortfalls regarding resilience-building against internal threats. Finally, we will provide some policy recommendations. More specifically, we will consider how the European Union is expected to strengthen submarine cables against internal attacks from cable providers.

Undersea cables as a potential battleground

In the past years, fears of disruption of undersea cables and data interception have led the European Union to question who should be allowed to build and manage its undersea infrastructure. More specifically, because of important concerns over the security of European data and its resilience against internal breaches the Union has become wary of collaborating with companies owned by strategic competitors. As a result, the European Commission endorsed the so-called New York Joint Statement on the security and resilience of undersea cables, stating that “managing security risks, including from high-risk suppliers of undersea cable equipment, and promoting best security practices for laying and maintaining these cables for secure and resilient global infrastructure is essential for the networks upon which the global economy relies.”[2] Importantly, the New York Statement clarifies a new type of strategic objective for the European Union. Previous policies mostly focused on cyber and physical attacks from third parties but did not consider the threats that could originate from internal providers. In today’s context, instead, the EU must focus on limiting potential threats from malicious partners in the supply and management of underwater cables while also planning against external attacks.

This development was made clear in the case of the Southeast Asia-Middle East-West Europe 6 cable. As we can deduct from the name, by early 2025 the project is expected to develop data connection between Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and West Europe through a structure of 19.200 km. Its landing points will touch 12 nations: France, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Pakistan, India, Maldives, Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Singapore, thus crucially strengthening connectivity levels between the European and Asian continents, crossing the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean.

“Submarine Cable Map.” Telegeography, September 23, 2024. https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Because of its geopolitical cruciality, the question of who would build and manage the SEA-ME-WE 6 has raised some deep-seated controversies between two powerful actors: the People’s Republic of China and the United States. Originally, the building tender was won by HMN Technologies, which presented an extremely cheap $500 million bid due to huge public subsidies from Beijing’s government.[3] As a result, Washington became worried of the influence that China would have gained over international data transmission had it won the competition. Reuters gathered evidence confirming that Washington pressured the consortium through a “carrot and stick” strategy for the appointment of New Jersey-based SubCom LLC as the winning company.[4] As a result, in February 2022 the consortium held a new building tender and, resultantly, ended all previous agreements with HMN Technologies. Of the three Chinese companies that were set to invest in the cable, two – China Telecommunications Corporation and China Mobile Ltd., accounting at 20% of the total investments – pulled out after Washington’s win. Shortly after, China Telecom, China Mobile, and China United Network Communications Group Co. Ltd. began designing an alternative cable that would connect the three continents through Hong Kong, Singapore, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and France.[5] The new infrastructure, known as EMA (Europe-Middle East-Asia), would provide Beijing with the fundamental advantage of creating a data transmission alternative that would prove fundamental in future confrontations with the US.

The SEA-ME-WE 6 case highlights a new dimension of the rivalry between China and the US. Both powers have been engaged for quite some time in a competition for leadership in the technological and defence sectors. This has been further accentuated by Xi Jinping’s decision of reorganizing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 2024 to strengthen the army’s cyber and intelligence capabilities. [6]

Central to this paper, however, is the effects that this subsea competition will have on the European Union. A fragmented data system will have deep security implications for the EU and its Member States, implications – we argue – that they are not sufficiently prepared to face. Firstly, the European Union will be more vulnerable to both physical and cyber-attacks in its maritime domain. Outside of its adjacent waters, the Union will feel the necessity to step up the securitisation of the Enlarged Mediterranean, particularly the area covering the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Here, other security threats have already destabilized old geopolitical equilibriums thus driving up the need to organise a concerted long-term strategy.

Secondly, the potential for an additional Chinese-made submarine cable touching down in the Union’s territory will require better security protocols against data breaches and divulgation. Besides strengthening underwater infrastructures from malicious external attacks, the Union is not ready to limit security risks originating from cable providers. HMN Tech’s closeness with the PCC and the PLA, as well as the 2018 National Intelligence Law which obliges all Chinese companies to cooperate with Beijing’s security system, will continue to endanger secure data transmission outside and within the Union’s borders.[7]

Analysis of current EU policies

The fragmentation of subsea cables will have major impacts on the European Union and its Member States. Especially so when diplomatic efforts behind the development and management of these infrastructures create situations of geopolitical instability. As the case of the SEA-ME-WE 6 shows, the rivalry between the United States and China is destined to grow as they recognise the cruciality of undersea cables for political, economic, and security interests. This will also have deep impacts for the European Union and the securitisation of its maritime infrastructure connecting it with Asia through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.

In April 2022 the European Parliament published an in-depth analysis of the current security threats to undersea cables. Among other aspects, the European Parliament fears that HMN Technologies and the growing Chinese tech sector might be used as a potential leverage for geopolitical purposes.[8] More specifically, the report finds that Beijing’s growing investments in the creation and management of submarine cables might have two harmful effects on the Union and its Member States: on the one side, the creation of a Chinese “monopoly” on submarine infrastructures which would increase already high levels of dependency. On the other side, the possibility of intercepting data and developing military technologies with deeply harmful consequences for the security of the Union.

Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0. European Parliament

The report also highlights a fundamental shortage of current European efforts and the overlap between diverse sectors – such as maritime security, cyber security, ocean governance, digital policy, and PESCO – in the protection and strengthening of these critical infrastructures. As a result, in the words of the European Parliament:

“[T]here is a high risk that cable resilience remains at the margins of policy discourse, and no agency is claiming immediate responsibility or authority since it sits in the intersections of different policies, mandates, and directorates.” [9]

From a security perspective, we can clearly see that the Union’s efforts are not sufficient to protect the EU and its Member States from internal attacks on submarine cables. The Strategic Compass only briefly mentions the need to protect crucial maritime infrastructure.[10] However, in the document, there is no specific reference to undersea cables, nor does it delineate a common security strategy for resilience-building against private providers. The first document to delineate a broad strategic blueprint for strengthening the resilience of the Union’s infrastructure is Council Recommendation 2023/C 20/01. However, the document falls short of drawing an effective response to potential internal threats against submarine cables. The Recommendation merely mentions the necessity for better assessments of risks without specifying how and in what form these should be conducted.[11]

From a maritime perspective too, the European Union is lacking a definite plan regarding undersea cables. The matter was considered by the revised EU Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) of 2023. In the document, the Council highlights how the Union

“[S]hould improve current risk and threat assessments on such infrastructures to stay up to date and complement them with response options and mitigating measures building on cross-sectoral expertise and capacities […] It is imperative to provide continued support to Member States to develop underwater protective assets, counter-drone solutions, and repair capabilities.”[12]

This necessity, in the words of the Council itself, originates from recent threats on underwater infrastructures, increasing cyber-attacks, and the hybridisation of conflicts. The revised EUMSS outlines an Action Plan to achieve better resilience and protection of maritime infrastructures. It requires Member States to promote regional projects, draw up risk assessment and contingency plans, conduct stress tests and maritime exercises, enhance cooperation between Member States, develop and deploy specialised vessels to patrol and protect maritime infrastructures and improve information sharing. Nonetheless, while attention on submarine infrastructure has surely grown, the Union still lacks a concerted and organised response against potential internal security threats.

From a cyber-security perspective, previous policies or legislation did not mention the need to protect undersea cables. Neither the first Network and Information Security (NIS) directive, implemented in 2018, nor the 2020 EU Cybersecurity Strategy considered the matter of submarine infrastructure. This gap was partly filled by the revised NIS directive of 2022, drafted with the objective of strengthening the Union’s resilience against cyber threats that might harm economic and security interests. Art. 2(d) of the document encourages Member States to adopt policies “related to sustaining the general availability, integrity and confidentiality of the public core of the open internet, including, where relevant, the cybersecurity of undersea communication cables.”[13] However, no specific strategic objectives are mentioned regarding internal providers.

More recently, the European Union has attempted to fill all remaining gaps through the Recommendation on Secure and Resilient Submarine Cable Infrastructure.[14] In the document, actions are divided between those to be conducted on a national basis and those handled at the Union level. In the first category, we find the promotion of high level of security in line with Directives NIS 1 and NIS 2; monitoring of cables; delivery of national risk assessments; stress testing; and quick administrative applications regarding planning, acquisition, construction, maintenance, and repair of submarine infrastructures

These are projects, proposed by the Member States, that should fill gaps in submarine cable infrastructure and contribute to increasing supply chain security for the protection of geostrategic interests of the Union and Member States alike. Importantly, these projects should be funded privately with partial support where necessary from the EU.

Recommendations

It is our opinion that current policies for the protection of undersea cables are not sufficient to affirm the Union and its Member States’ security interests against internal threats. Neither security, maritime, nor cyber policies effectively account for internal attacks on submarine infrastructures thus leaving data traveling between Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia partly unprotected. As a result, we argue, undersea cables are vulnerable to security attacks originating not only from malicious external actors but also from providers. To prevent this, the European Union must draw a unified and effective policy for the protection of its data and the development of infrastructure resilience.

Firstly, the European Union must consider creating a unitary policy concerning submarine infrastructures. As we have seen before, as of today EU regulations, recommendations, and directives are scattered between multiple sectors. While the protection of undersea cables is most definitely a complicated matter that stretches over a variety of policy areas, a single pyramid-like approach would go a long way in filling all existing gaps and avoiding confusion. Moreover, because the control and management of undersea infrastructures remains for the most part in the hands of single Member States, a unitary policy could increase levels of awareness and cooperation between national systems. Risk assessment, surveillance of suspicious activities, and information sharing are key aspects of an undersea infrastructure that is ready to withstand both internal and external threats.

Secondly, the European Union must increase the level of coordination between Member States. The current development of Chinese-made infrastructure, especially considering the future EMA cable touching on European soil, necessarily requires Member States to create and organise a concerted response not only against cyber-attacks from outside actors but also from those building and managing said infrastructures. The EU Parliament itself recognises the possibility of future crises as “HMN Technologies controlling shareholder Hengtong’s joint venture lab with PLA cyber intelligence affiliated entity increases the risk of espionage and improves China’s access to sensitive information as both diplomatic and military communication travels through privately-owned undersea cable provided by Chinese companies.”

Nonetheless, current EU policies are not ready to face such challenges.[15] All previously considered documents outline responses tailor-made for attacks from third parties. While fundamental for the protection of EU confidential data, this structure is currently insufficient to assure resilience against commercial providers. As a result, Member States should increase their responsiveness against internal threats by thoroughly analysing their commercial partners and identifying their leverage on submarine infrastructure and the data passing through it. On its part, the European Union should impose more stringent investment regulations and provide for a security system that is more capable of responding to malicious internal attacks. The European Parliament resolution on the security challenges in the Indo-Pacific specifically mentions the necessity of securing an attractive alternative to the Chinese connectivity strategy and encourages connectivity cooperation with partners in the Indo-Pacific against new security challenges, including possible physical and cyber-attacks against undersea cables.[16] Starting from this, European Institutions should work for the creation of regional policies in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean that consider the threat posed by companies owned by strategic competitors.

Subsequently, it is our view that the European Union should invest more in Cable Projects of European Interest tailored against potential internal attacks. The Union must be able to draft a list of common priorities of geostrategic importance that cannot be handled by the private sector alone. Through information sharing and a standardisation of risk assessment and stress tests, Member States would thus be able to propose to the Commission projects that increase the performance of submarine infrastructures and respond to a variety of threats. However, we believe that as the Union and its Members realise the importance of highly resilient submarine infrastructures, the funding of these projects should shift more on the Union’s side. As of now, private financing remains the main source of economic support for CPEIs. We argue that for projects that have direct geostrategic effects on the Union, EU Institutions should step up their economic involvement.

Finally, the long-term strategic objective of the European Union should be to achieve a higher level of technological independence. As Mario Draghi has highlighted in his report, “Europe must react to a world of less stable geopolitics, where dependencies are becoming vulnerabilities, and it can no longer rely on others for its security.”[17] While at this stage it is inconceivable that the EU will become a leading international cable provider, it is fundamental that the Union realises the costs and risks of depending on others for the transportation and management of data. While, therefore, expanding as much as possible the internal sector for cable production – which can count on some excellent providers such as Prysmian (Italy), Nexans (France), and Leoni (Germany) – the Union and its Member States should regulate more strictly what providers can access the UE cable market and how they should do so. Analysing these companies’ impingements on European security interests and improving control on Foreign Direct Investments will play a fundamental role in strengthening UE data sovereignty.

[1] Telegeography (2024). “Submarine Cables.” Telegeography. Accessed October 4, 2024 https://www2.telegeography.com/submarine-cable-faqs-frequently-asked-questions

[2] “Joint Statement on the Security and Resilience of Undersea Cables in a Globally Digitalised World.” Endorsed by the United States of America, Australia, Canada, the European Union, the Federated States of Micronesia, Finland, France, Japan, the Marshall Islands, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Tonga, Tuvalu, and the United Kingdom. 79th annual United National General Assembly, September 26th, 2024.

[3] Brock, Joe (2023). “U.S. and China Wage War Beneath the Waves – Over Internet Cables.” Reuters, March 24, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/us-china-tech-cables/

[4] Ibidem

[5] Brock, Joe (2023). “China Plans $500 Million Subsea Internet Cable to Rival US-backed Project.” Reuters, April 6, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-plans-500-mln-subsea-internet-cable-rival-us-backed-project-2023-04-06/

[6] Nouwens, Meia (2024). “China’s New Information Support Force.” International Institute for Strategic Studies, May 3 https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2024/05/chinas-new-information-support-force/

[7] “National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic of China.” Adopted at the 28th session of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress on June 27, 2017; amended in accordance with the “Decision on Amending the P.R.C. Frontier Health and Quarantine Law and Five Other Laws” by the 2nd session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress on April 27, 2018.

[8] Bueger, Christian, Liebetrau, Tobias, and Franken, Jonas (2022). “Security Threats to Undersea Communications Cables and Infrastructure – Consequences for the EU.” No. PE 702.557, Brussels, June 2022.

[9] European Parliament (2022). “The EU and the Security Challenges in the Indo-Pacific”. No PE 2022/0224, Brussels, June 7, 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0224_EN.html.

[10] General Secretariat of the Council (Council of the European Union) (2022). “A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence”. No. 7371/22, Brussels, March 21, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7371-2022-INIT/en/pdf

[11] Council of the European Union (2023). “Council Recommendation of 8 December 2022 on a Union-wide Coordinated Approach to Strengthen the Resilience of Critical Infrastructure.” No. 2023/C 20/01, Brussels, December 8 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023H0120%2801%29

[12] Council of the European Union (2023). “Council Conclusions on the Revised EU Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) and its Action Plan.” No. 14280/23, Brussels, October 24 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/67499/st14280-en23.pdf

[13] Council of the European Union and European Parliament (2022). “Directive 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on Measures for a High Common Level of Cybersecurity Across the Union, Amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972, and Repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148 (NIS 2 Directive).” No 2022/2555, Brussels, December 14, 2022. [Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555/oj

[14] European Commission (2024). “Commission Recommendation of 26 February 2024 on Secure and Resilient Submarine Cable Infrastructures.” No. C(2024) 1181 final, Brussels, February 26, 2024 https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7087-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[15] European Commission (2024). “Commission Recommendation of 26 February 2024 on Secure and Resilient Submarine Cable Infrastructures.” No. C(2024) 1181 final, Brussels, February 26, 2024 https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7087-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[16] European Parliament (2022). “The EU and the Security Challenges in the Indo-Pacific”. No PE 2022/0224, Brussels, June 7, 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0224_EN.html

[17] Draghi, Mario (2024). “The Future of EU Competitiveness”. September 2024.